Using archived and newly generated RXTE light curves#

Learning Goals#

By the end of this tutorial, you will:

Know how to find and use observation tables hosted by HEASARC.

Be able to search for RXTE observations of a named source.

Understand how to access RXTE light curves stored in the HEASARC AWS S3 bucket.

Be capable of downloading and visualizing retrieved light curves.

Know how to generate new RXTE-PCA light curves with:

Custom energy bounds.

Higher temporal resolution than archived products.

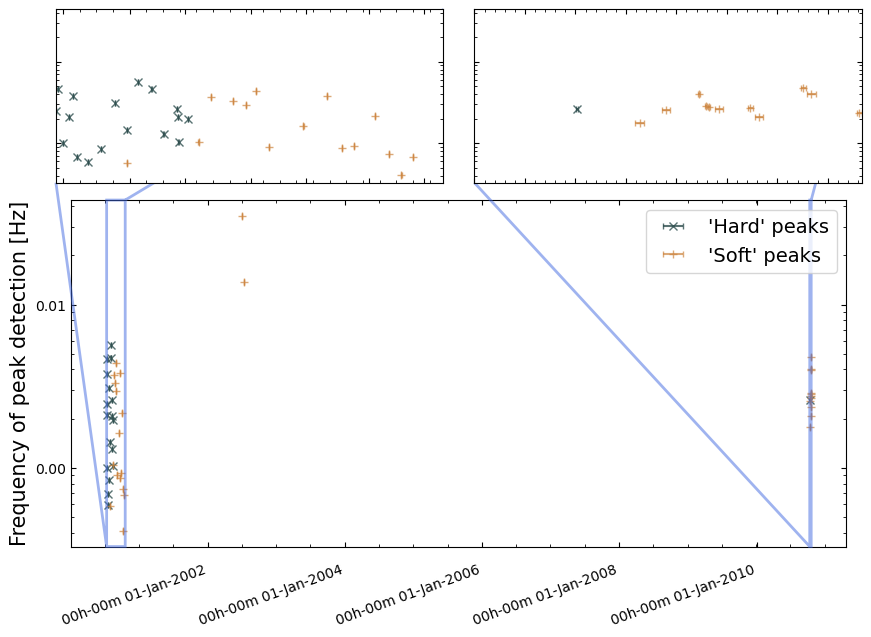

Use ‘Continuous Wavelet Transform’ (CWT) peak finding to identify possible bursts.

Introduction#

This notebook is intended to demonstrate how you can use Rossi Timing X-ray Explorer (RXTE) data to examine the temporal variation of a source’s X-ray emission across a wide energy range. We start by identifying and exploring archived RXTE light curves for our source of interest and move on to generating new light curves from raw RXTE Proportional Counter Array (PCA) data.

RXTE was a high-energy mission that provided very high temporal resolution, moderate spectral resolution, observations across a wide energy band (~2–250 keV).

The satellite hosted three instruments:

PCA - Proportional Counter Array; a set of five co-aligned proportional counter units (PCU), sensitive in the 2–60 keV energy band. Collimated ~1 degree full-width half-maximum (FWHM) field-of-view (FoV).

HEXTE - High-Energy X-ray Timing Experiment; a pair of scintillation-counter clusters, sensitive in the 15–250 keV energy band. Collimated ~1 degree FWHM FoV.

ASM - All Sky Monitor; a set of three coded-mask instruments that covered a significant fraction of the sky with each observation (each camera had a 6 x 90 degree FoV). Sensitive in the 2–12 keV energy band.

The PCA and HEXTE instruments had maximum temporal resolutions of \(1 \mu \rm{s}\) and \(8 \mu \rm{s}\) respectively.

Our demonstration is only going to use data from the PCA and HEXTE instruments, and we will only generate new light curves from the PCA instrument.

Though neither PCA nor HEXTE had any imaging capability (they collected photons from their whole FoV without any further spatial information), their time resolution was such that they were very well suited to observations of pulsars; rotating neutron stars with high-energy emission that can vary on the millisecond scale.

We’re going to use a particularly notable pulsar in a low-mass X-ray binary (LMXB) system discovered using RXTE as the subject of our demonstration, ‘IGR J17480–2446’ or ‘T5X2’.

Though it actually rotates quite slowly for a pulsar (“only” ~11 times per second), it displays a number of very interesting behaviors; these include ‘bursts’ of emission caused by infalling gas from its binary companion, and X-ray emission caused by sustained thermonuclear reactions from a large build-up of material possible because of the high accretion rate from its companion.

This behavior had been predicted and modeled, but the first real example was identified in RXTE observations of T5X2, see M. Linares et al. (2012) for full analysis and results.

Inputs#

The name of the source we’ve chosen for the demonstration; IGR J17480–2446 or T5X2.

Outputs#

Visualizations of archived RXTE-PCA and HEXTE light curves.

Newly generated RXTE-PCA light curves within a custom energy band.

Newly generated RXTE-PCA light curves with a higher time resolution than the archived data products.

Runtime#

As of 21st January 2026, this notebook takes ~25 minutes to run to completion on Fornax, using the ‘small’ server with 8GB RAM / 2 cores.

Imports & Environments#

import contextlib

import glob

import multiprocessing as mp

import os

from pprint import pprint

from typing import List, Tuple, Union

import heasoftpy as hsp

import matplotlib.dates as mdates

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from astropy.coordinates import SkyCoord

from astropy.io import fits

from astropy.table import unique

from astropy.time import Time

from astropy.units import Quantity

from astroquery.heasarc import Heasarc

from matplotlib import cm

from matplotlib.colors import Normalize

from matplotlib.ticker import FuncFormatter

from s3fs import S3FileSystem

from scipy.signal import find_peaks_cwt

from xga.products import AggregateLightCurve, LightCurve

/opt/envs/heasoft/lib/python3.12/site-packages/xga/utils.py:39: DeprecationWarning: The XGA 'find_all_wcs' function should be imported from imagetools.misc, in the future it will be removed from utils.

warn(message, DeprecationWarning)

/opt/envs/heasoft/lib/python3.12/site-packages/xga/utils.py:619: UserWarning: SAS_DIR environment variable is not set, unable to verify SAS is present on system, as such all functions in xga.sas will not work.

warn("SAS_DIR environment variable is not set, unable to verify SAS is present on system, as such "

/opt/envs/heasoft/lib/python3.12/site-packages/xga/__init__.py:6: UserWarning: This is the first time you've used XGA; to use most functionality you will need to configure /home/jovyan/.config/xga/xga.cfg to match your setup, though you can use product classes regardless.

from .utils import xga_conf, CENSUS, OUTPUT, NUM_CORES, XGA_EXTRACT, BASE_XSPEC_SCRIPT, CROSS_ARF_XSPEC_SCRIPT, \

/opt/envs/heasoft/lib/python3.12/site-packages/xga/products/relation.py:12: DeprecationWarning: `scipy.odr` is deprecated as of version 1.17.0 and will be removed in SciPy 1.19.0. Please use `https://pypi.org/project/odrpack/` instead.

import scipy.odr as odr

/opt/envs/heasoft/lib/python3.12/site-packages/xga/utils.py:619: UserWarning: SAS_DIR environment variable is not set, unable to verify SAS is present on system, as such all functions in xga.sas will not work.

warn("SAS_DIR environment variable is not set, unable to verify SAS is present on system, as such "

/opt/envs/heasoft/lib/python3.12/site-packages/xga/__init__.py:6: UserWarning: This is the first time you've used XGA; to use most functionality you will need to configure /home/jovyan/.config/xga/xga.cfg to match your setup, though you can use product classes regardless.

from .utils import xga_conf, CENSUS, OUTPUT, NUM_CORES, XGA_EXTRACT, BASE_XSPEC_SCRIPT, CROSS_ARF_XSPEC_SCRIPT, \

/opt/envs/heasoft/lib/python3.12/site-packages/xga/products/relation.py:12: DeprecationWarning: `scipy.odr` is deprecated as of version 1.17.0 and will be removed in SciPy 1.19.0. Please use `https://pypi.org/project/odrpack/` instead.

import scipy.odr as odr

Global Setup#

Functions#

Constants#

Configuration#

1. Finding the data#

To identify relevant RXTE data, we could use Xamin, the HEASARC web portal, the Virtual Observatory (VO) python client pyvo, or the Astroquery module (our choice for this demonstration).

Using Astroquery to find the RXTE observation summary (master) table#

Using the Heasarc object from Astroquery, we can easily search through all of HEASARC’s catalog holdings. In this

case we need to find what we refer to as a ‘master’ catalog/table, which summarizes all RXTE observations present in

our archive. We can do this by passing the master=True keyword argument to the list_catalogs method.

table_name = Heasarc.list_catalogs(keywords="xte", master=True)[0]["name"]

table_name

np.str_('xtemaster')

Identifying RXTE observations of IGR J17480–2446/T5X2#

Now that we have identified the HEASARC table that contains information on RXTE pointings, we’re going to search it for observations of T5X2.

For convenience, we pull the coordinate of T5X2/IGR J17480–2446 from the Strasbourg astronomical Data Center (CDS) name

resolver functionality built into Astropy’s SkyCoord class. A constant containing the name of the target was created in

the ‘Global Setup: Constants’ section of this notebook:

SRC_NAME

'IGR J17480–2446'

Using the SkyCoord class, we can fetch the coordinates for our target:

# Get the coordinate for our source

rel_coord = SkyCoord.from_name(SRC_NAME)

# Turn it into a straight Astropy quantity, which will be useful later

rel_coord_quan = Quantity([rel_coord.ra, rel_coord.dec])

rel_coord

<SkyCoord (ICRS): (ra, dec) in deg

(267.0201292, -24.7802417)>

Hint

Each HEASARC catalog has its own default search radius, which you can retrieve

using Heasarc.get_default_radius(catalog_name) - you should carefully consider the

search radius you use for your own science case!

Then we can use the query_region method of Heasarc to search for relevant RXTE observations:

all_obs = Heasarc.query_region(rel_coord, catalog=table_name)

all_obs

| obsid | prnb | status | pi_lname | pi_fname | target_name | ra | dec | time | duration | exposure | __row |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| deg | deg | d | s | s | |||||||

| object | int32 | object | object | object | object | float64 | float64 | float64 | float64 | float64 | object |

| 93055 | accepted | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | EXO1745-248 | 267.2333 | -24.8950 | -- | -- | -- | 70727 | |

| 50054-06-01-01 | 50054 | archived | ZHANG | WILLIAM | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51749.63341 | 5820 | 2429 | 71046 |

| 50054-06-01-00 | 50054 | archived | ZHANG | WILLIAM | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51746.43203 | 6047 | 3434 | 71047 |

| 50138-03-01-00 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51738.18831 | 3260 | 1680 | 71048 |

| 50138-03-01-01 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51738.73752 | 3217 | 1735 | 71049 |

| 50138-03-02-00 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51740.0494 | 2940 | 1064 | 71050 |

| 50138-03-02-01 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51740.11606 | 541 | -- | 71051 |

| 50138-03-03-00 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51741.44572 | 5237 | 3378 | 71052 |

| 50138-03-04-00 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51742.50841 | 4596 | 3477 | 71053 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 96316-01-16-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55684.96769 | 2770 | 1917 | 71196 |

| 96316-01-17-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55691.58411 | 4860 | 1667 | 71197 |

| 96316-01-18-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55697.92324 | 4419 | 2101 | 71198 |

| 96316-01-19-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55704.84321 | 4554 | 2130 | 71199 |

| 96316-01-20-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55711.75772 | 3631 | 1622 | 71200 |

| 96316-01-21-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55718.35848 | 4744 | 2013 | 71201 |

| 96316-01-22-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55725.37816 | 3388 | 2213 | 71202 |

| 96316-01-23-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55731.20844 | 4067 | 2078 | 71203 |

| 96316-01-24-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55739.64314 | 4437 | 1933 | 71204 |

We can immediately see that the first entry in the all_obs table does not have

an ObsID, and is also missing other crucial information such as when the observation

was taken, and how long the exposure was. This is because a proposal was accepted, but

the data were never taken. In this case it’s likely because the proposal was for a

target of opportunity (ToO), and the trigger conditions were never met.

All that said, we should filter our table of observations to ensure that only real observations are included. The easiest way to do that is probably to require that the exposure time entry is greater than zero:

valid_obs = all_obs[all_obs["exposure"] > 0]

valid_obs

| obsid | prnb | status | pi_lname | pi_fname | target_name | ra | dec | time | duration | exposure | __row |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| deg | deg | d | s | s | |||||||

| object | int32 | object | object | object | object | float64 | float64 | float64 | float64 | float64 | object |

| 50054-06-01-01 | 50054 | archived | ZHANG | WILLIAM | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51749.63341 | 5820 | 2429 | 71046 |

| 50054-06-01-00 | 50054 | archived | ZHANG | WILLIAM | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51746.43203 | 6047 | 3434 | 71047 |

| 50138-03-01-00 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51738.18831 | 3260 | 1680 | 71048 |

| 50138-03-01-01 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51738.73752 | 3217 | 1735 | 71049 |

| 50138-03-02-00 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51740.0494 | 2940 | 1064 | 71050 |

| 50138-03-03-00 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51741.44572 | 5237 | 3378 | 71052 |

| 50138-03-04-00 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51742.50841 | 4596 | 3477 | 71053 |

| 50138-03-05-00 | 50138 | archived | SWANK | JEAN | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51743.57614 | 4176 | 3038 | 71054 |

| 50054-06-02-01 | 50054 | archived | ZHANG | WILLIAM | EXO_1745-248 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 51756.25972 | 4793 | 3539 | 71055 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 96316-01-16-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55684.96769 | 2770 | 1917 | 71196 |

| 96316-01-17-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55691.58411 | 4860 | 1667 | 71197 |

| 96316-01-18-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55697.92324 | 4419 | 2101 | 71198 |

| 96316-01-19-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55704.84321 | 4554 | 2130 | 71199 |

| 96316-01-20-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55711.75772 | 3631 | 1622 | 71200 |

| 96316-01-21-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55718.35848 | 4744 | 2013 | 71201 |

| 96316-01-22-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55725.37816 | 3388 | 2213 | 71202 |

| 96316-01-23-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55731.20844 | 4067 | 2078 | 71203 |

| 96316-01-24-00 | 96316 | archived | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | TERZAN_5 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 55739.64314 | 4437 | 1933 | 71204 |

Then, by converting the ‘time’ column of the valid observations table into an Astropy

Time object, and using the min() and max() methods, we can see that the

observations we’ve selected come from a period of over 10 years.

valid_obs_times = Time(valid_obs["time"], format="mjd")

valid_obs_datetimes = valid_obs_times.to_datetime()

print(valid_obs_datetimes.min())

print(valid_obs_datetimes.max())

2000-07-13 04:31:09.984000

2011-11-19 14:08:29.472000

To reduce the run time of this demonstration, we’ll select observations taken before the 19th of October 2010. There are a significant number of observations taken after this date, but the light curves are not as featureful and interesting as those taken before.

cut_valid_obs = valid_obs[valid_obs_times < Time("2010-10-19")]

rel_obsids = np.array(cut_valid_obs["obsid"])

print(len(rel_obsids))

62

Constructing an ADQL query [advanced alternative]#

Alternatively, if you wished to place extra constraints on the search, you could use the more complex but more powerful

query_tap method to pass a full Astronomical Data Query Language (ADQL) query. This demonstration runs the same

spatial query as before but also includes a stringent exposure time requirement; you might do this to try and only

select the highest signal-to-noise observations.

Note that we call the to_table method on the result of the query to convert the result into an Astropy table, which

is the form required to pass to the locate_data method (see the next section).

query = (

"SELECT * "

"from {c} as cat "

"where contains(point('ICRS',cat.ra,cat.dec), circle('ICRS',{ra},{dec},0.0033))=1 "

"and cat.exposure > 0".format(

ra=rel_coord.ra.value, dec=rel_coord.dec.value, c=table_name

)

)

alt_obs = Heasarc.query_tap(query).to_table()

alt_obs

| __row | pi_lname | pi_fname | pi_no | prnb | cycle | subject_category | target_name | time_awarded | ra | dec | priority | tar_no | obsid | time | duration | exposure | status | scheduled_date | observed_date | processed_date | archived_date | hexte_anglea | hexte_angleb | hexte_dwella | hexte_dwellb | hexte_energya | hexte_energyb | hexte_modea | hexte_modeb | pca_config1 | pca_config2 | pca_config3 | pca_config4 | pca_config5 | pca_config6 | lii | bii | __x_ra_dec | __y_ra_dec | __z_ra_dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | deg | deg | d | s | s | d | d | d | d | deg | deg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| object | object | object | int32 | int32 | int16 | object | object | float64 | float64 | float64 | int16 | int16 | object | float64 | float64 | float64 | object | float64 | float64 | int32 | int32 | object | object | object | object | object | object | object | object | object | object | object | object | object | object | float64 | float64 | float64 | float64 | float64 |

| 71046 | ZHANG | WILLIAM | 164 | 50054 | 5 | LMXB | EXO_1745-248 | 200000.0 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 1 | 6 | 50054-06-01-01 | 51749.63341 | 5820 | 2429 | archived | 51749.63341 | 51749.63341 | -- | 52129 | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8US_256_DX0F | E_8US_256_DX0F | STANDARD1 | STANDARD2 | E_125US_64M_0_1S | TLA_1S_10_249_1S_10000_F | CB_125US_1M_0_249_H | IDLE | 3.8381 | 1.6836 | -0.906683970297968 | -0.0471604275070132 | -0.419165924285443 |

| 71047 | ZHANG | WILLIAM | 164 | 50054 | 5 | LMXB | EXO_1745-248 | 200000.0 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 1 | 6 | 50054-06-01-00 | 51746.43203 | 6047 | 3434 | archived | 51746.43203 | 51746.43203 | -- | 52122 | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8US_256_DX0F | E_8US_256_DX0F | STANDARD1 | STANDARD2 | E_125US_64M_0_1S | TLA_1S_10_249_1S_10000_F | CB_125US_1M_0_249_H | IDLE | 3.8381 | 1.6836 | -0.906683970297968 | -0.0471604275070132 | -0.419165924285443 |

| 71048 | SWANK | JEAN | 168 | 50138 | 5 | OTHER | EXO_1745-248 | 15000.0 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 1 | 3 | 50138-03-01-00 | 51738.18831 | 3260 | 1680 | archived | 51738.18831 | 51738.18831 | -- | 52122 | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8US_256_DX1F | E_8US_256_DX1F | STANDARD1 | STANDARD2 | TLA_1S_10_249_1S_5000_F | CB_125US_1M_0_249_H | CB_8MS_64M_0_249_H | E_125US_64M_0_1S | 3.8381 | 1.6836 | -0.906683970297968 | -0.0471604275070132 | -0.419165924285443 |

| 71049 | SWANK | JEAN | 168 | 50138 | 5 | OTHER | EXO_1745-248 | 15000.0 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 1 | 3 | 50138-03-01-01 | 51738.73752 | 3217 | 1735 | archived | 51738.73752 | 51738.73752 | -- | 52122 | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8US_256_DX1F | E_8US_256_DX1F | STANDARD1 | STANDARD2 | TLA_1S_10_249_1S_5000_F | CB_125US_1M_0_249_H | CB_8MS_64M_0_249_H | E_125US_64M_0_1S | 3.8381 | 1.6836 | -0.906683970297968 | -0.0471604275070132 | -0.419165924285443 |

| 71050 | SWANK | JEAN | 168 | 50138 | 5 | OTHER | EXO_1745-248 | 15000.0 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 1 | 3 | 50138-03-02-00 | 51740.0494 | 2940 | 1064 | archived | 51740.0494 | 51740.0494 | -- | 52122 | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8US_256_DX1F | E_8US_256_DX1F | STANDARD1 | STANDARD2 | TLA_1S_10_249_1S_5000_F | CB_125US_1M_0_249_H | CB_8MS_64M_0_249_H | E_125US_64M_0_1S | 3.8381 | 1.6836 | -0.906683970297968 | -0.0471604275070132 | -0.419165924285443 |

| 71052 | SWANK | JEAN | 168 | 50138 | 5 | OTHER | EXO_1745-248 | 15000.0 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 1 | 3 | 50138-03-03-00 | 51741.44572 | 5237 | 3378 | archived | 51741.44572 | 51741.44572 | -- | 52122 | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8US_256_DX1F | E_8US_256_DX1F | STANDARD1 | STANDARD2 | TLA_1S_10_249_1S_5000_F | CB_125US_1M_0_249_H | CB_8MS_64M_0_249_H | E_125US_64M_0_1S | 3.8381 | 1.6836 | -0.906683970297968 | -0.0471604275070132 | -0.419165924285443 |

| 71053 | SWANK | JEAN | 168 | 50138 | 5 | OTHER | EXO_1745-248 | 15000.0 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 1 | 3 | 50138-03-04-00 | 51742.50841 | 4596 | 3477 | archived | 51742.50841 | 51742.50841 | -- | 52122 | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8US_256_DX1F | E_8US_256_DX1F | STANDARD1 | STANDARD2 | TLA_1S_10_249_1S_5000_F | CB_125US_1M_0_249_H | CB_8MS_64M_0_249_H | E_125US_64M_0_1S | 3.8381 | 1.6836 | -0.906683970297968 | -0.0471604275070132 | -0.419165924285443 |

| 71054 | SWANK | JEAN | 168 | 50138 | 5 | OTHER | EXO_1745-248 | 15000.0 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 1 | 3 | 50138-03-05-00 | 51743.57614 | 4176 | 3038 | archived | 51743.57614 | 51743.57614 | -- | 52122 | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8US_256_DX1F | E_8US_256_DX1F | STANDARD1 | STANDARD2 | TLA_1S_10_249_1S_5000_F | CB_125US_1M_0_249_H | CB_8MS_64M_0_249_H | E_125US_64M_0_1S | 3.8381 | 1.6836 | -0.906683970297968 | -0.0471604275070132 | -0.419165924285443 |

| 71055 | ZHANG | WILLIAM | 164 | 50054 | 5 | LMXB | EXO_1745-248 | 200000.0 | 267.0225 | -24.7819 | 1 | 6 | 50054-06-02-01 | 51756.25972 | 4793 | 3539 | archived | 51756.25972 | 51756.25972 | -- | 52151 | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8US_256_DX0F | E_8US_256_DX0F | STANDARD1 | STANDARD2 | E_125US_64M_0_1S | TLA_1S_10_249_1S_10000_F | CB_125US_1M_0_249_H | IDLE | 3.8381 | 1.6836 | -0.906684262535712 | -0.0471604427075212 | -0.419165290444834 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 71196 | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | 530 | 96316 | 15 | LMXB | TERZAN_5 | 1920.0 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 0 | 1 | 96316-01-16-00 | 55684.96769 | 2770 | 1917 | archived | 55684.96769 | 55684.96769 | 55693 | -- | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8us_256_DX1F | E_8us_256_DX1F | GOODXENON1_2S | GOODXENON2_2S | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | STANDARD1B | STANDARD2F | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | 3.8389 | 1.6859 | -0.906696760092206 | -0.0471877504630087 | -0.419135182780613 |

| 71197 | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | 530 | 96316 | 15 | LMXB | TERZAN_5 | 1670.0 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 0 | 1 | 96316-01-17-00 | 55691.58411 | 4860 | 1667 | archived | 55691.58411 | 55691.58411 | 55699 | -- | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8us_256_DX1F | E_8us_256_DX1F | GOODXENON1_2S | GOODXENON2_2S | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | STANDARD1B | STANDARD2F | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | 3.8389 | 1.6859 | -0.906696760092206 | -0.0471877504630087 | -0.419135182780613 |

| 71198 | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | 530 | 96316 | 15 | LMXB | TERZAN_5 | 2100.0 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 0 | 1 | 96316-01-18-00 | 55697.92324 | 4419 | 2101 | archived | 55697.92324 | 55697.92324 | 55705 | -- | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8us_256_DX1F | E_8us_256_DX1F | GOODXENON1_2S | GOODXENON2_2S | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | STANDARD1B | STANDARD2F | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | 3.8389 | 1.6859 | -0.906696760092206 | -0.0471877504630087 | -0.419135182780613 |

| 71199 | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | 530 | 96316 | 15 | LMXB | TERZAN_5 | 2130.0 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 0 | 1 | 96316-01-19-00 | 55704.84321 | 4554 | 2130 | archived | 55704.84321 | 55704.84321 | 55712 | -- | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8us_256_DX1F | E_8us_256_DX1F | GOODXENON1_2S | GOODXENON2_2S | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | STANDARD1B | STANDARD2F | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | 3.8389 | 1.6859 | -0.906696760092206 | -0.0471877504630087 | -0.419135182780613 |

| 71200 | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | 530 | 96316 | 15 | LMXB | TERZAN_5 | 1620.0 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 0 | 1 | 96316-01-20-00 | 55711.75772 | 3631 | 1622 | archived | 55711.75772 | 55711.75772 | 55719 | -- | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8us_256_DX1F | E_8us_256_DX1F | GOODXENON1_2S | GOODXENON2_2S | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | STANDARD1B | STANDARD2F | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | 3.8389 | 1.6859 | -0.906696760092206 | -0.0471877504630087 | -0.419135182780613 |

| 71201 | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | 530 | 96316 | 15 | LMXB | TERZAN_5 | 2010.0 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 0 | 1 | 96316-01-21-00 | 55718.35848 | 4744 | 2013 | archived | 55718.35848 | 55718.35848 | 55726 | -- | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8us_256_DX1F | E_8us_256_DX1F | GOODXENON1_2S | GOODXENON2_2S | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | STANDARD1B | STANDARD2F | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | 3.8389 | 1.6859 | -0.906696760092206 | -0.0471877504630087 | -0.419135182780613 |

| 71202 | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | 530 | 96316 | 15 | LMXB | TERZAN_5 | 2210.0 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 0 | 1 | 96316-01-22-00 | 55725.37816 | 3388 | 2213 | archived | 55725.37816 | 55725.37816 | 55733 | -- | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8us_256_DX1F | E_8us_256_DX1F | GOODXENON1_2S | GOODXENON2_2S | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | STANDARD1B | STANDARD2F | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | 3.8389 | 1.6859 | -0.906696760092206 | -0.0471877504630087 | -0.419135182780613 |

| 71203 | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | 530 | 96316 | 15 | LMXB | TERZAN_5 | 2080.0 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 0 | 1 | 96316-01-23-00 | 55731.20844 | 4067 | 2078 | archived | 55731.20844 | 55731.20844 | 55739 | -- | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8us_256_DX1F | E_8us_256_DX1F | GOODXENON1_2S | GOODXENON2_2S | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | STANDARD1B | STANDARD2F | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | 3.8389 | 1.6859 | -0.906696760092206 | -0.0471877504630087 | -0.419135182780613 |

| 71204 | ALTAMIRANO | DIEGO | 530 | 96316 | 15 | LMXB | TERZAN_5 | 1930.0 | 267.0208 | -24.7800 | 0 | 1 | 96316-01-24-00 | 55739.64314 | 4437 | 1933 | archived | 55739.64314 | 55739.64314 | 55749 | -- | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | DEFAULT | E_8us_256_DX1F | E_8us_256_DX1F | GOODXENON1_2S | GOODXENON2_2S | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | STANDARD1B | STANDARD2F | D_1US_0_249_1024_64S_F | 3.8389 | 1.6859 | -0.906696760092206 | -0.0471877504630087 | -0.419135182780613 |

Using Astroquery to fetch datalinks to RXTE datasets#

We’ve already figured out which HEASARC table to pull RXTE observation information from, and then used that table to identify specific observations that might be relevant to our target source (T5X2). Our next step is to pinpoint the exact locations of each observation’s data files.

Just as in the last two steps, we’re going to make use of Astroquery. The difference is, rather than dealing with tables of observations, we now need to construct ‘datalinks’ to places where specific files for each observation are stored. In this demonstration we’re going to pull data from the HEASARC ‘S3 bucket’, an Amazon-hosted open-source dataset containing all of HEASARC’s data holdings.

For our use case, we’re going to exclude any data links that point to data directories containing non-pointing portions of RXTE observations; in practise that means data collected during slewing before and after the observation of our target. Slewing data can be more difficult to work with, so for this demonstration we’re going to ignore it. The data links tell us which directories contain such data through the final character of the directory name:

A - Slewing data from before the observation.

Z - Slewing data from after the observation.

S - Data taken in scan mode.

R - Data taken in a raster grid mode.

See also

This HEASARC page details the standard contents of RXTE observation directories, as well as the standard names of files and sub-directories. Section 3.3 explains the meanings of the characters we discussed above.

data_links = Heasarc.locate_data(cut_valid_obs, "xtemaster")

# Drop rows with duplicate AWS links

data_links = unique(data_links, keys="aws")

# Drop rows that represent directories of slewing, scanning, or raster scanning

# observation data

non_pnting = (

np.char.endswith(data_links["aws"].value[..., None], ["Z/", "A/", "S/", "R/"]).sum(

axis=1

)

== 0

)

data_links = data_links[non_pnting]

data_links[-10:]

| ID | access_url | sciserver | aws | content_length | error_message |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| byte | |||||

| object | object | str50 | str63 | int64 | object |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71049 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138//50138-03-01-01/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-01-01/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-01-01/ | -- | |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71050 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138//50138-03-02-00/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-02-00/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-02-00/ | -- | |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71052 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138//50138-03-03-00/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-03-00/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-03-00/ | -- | |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71053 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138//50138-03-04-00/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-04-00/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-04-00/ | -- | |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71054 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138//50138-03-05-00/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-05-00/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03-05-00/ | -- | |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71048 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138//50138-03/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO5/P50138/50138-03/ | -- | |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71147 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412//70412-01-01-00/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412/70412-01-01-00/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412/70412-01-01-00/ | -- | |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71082 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412//70412-01-02-00/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412/70412-01-02-00/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412/70412-01-02-00/ | -- | |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71081 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412//70412-01-03-00/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412/70412-01-03-00/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412/70412-01-03-00/ | -- | |

| ivo://nasa.heasarc/xtemaster?71081 | https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/FTP/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412//70412-01/ | /FTP/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412/70412-01/ | s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO7/P70412/70412-01/ | -- |

2. Acquiring the data#

We now know where the relevant RXTE light curves are stored in the HEASARC S3 bucket and will proceed to download them for local use.

The easiest way to download data#

At this point, you may wish to simply download the entire set of files for all the observations you’ve identified.

That is easily achieved using Astroquery, with the download_data method of Heasarc, we just need to pass

the datalinks we found in the previous step.

We demonstrate this approach using the first three entries in the datalinks table, but in the following sections will demonstrate a more complicated, but targeted, approach that will let us download the light curve files only:

Heasarc.download_data(data_links[:3], host="aws", location=ROOT_DATA_DIR)

INFO: Downloading data AWS S3 ... [astroquery.heasarc.core]

INFO: Enabling anonymous cloud data access ... [astroquery.heasarc.core]

INFO: downloading s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-01-00/ [astroquery.heasarc.core]

INFO: downloading s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-02-00/ [astroquery.heasarc.core]

INFO: downloading s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-02-01/ [astroquery.heasarc.core]

INFO: downloading s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-01-00/ [astroquery.heasarc.core]

INFO: downloading s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-02-00/ [astroquery.heasarc.core]

INFO: downloading s3://nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-02-01/ [astroquery.heasarc.core]

Downloading only the archived RXTE light curves#

Rather than downloading all files for all our observations, we will now only fetch those that are directly relevant to what we want to do in this notebook - this method is a little more involved than using Astroquery, but it is more efficient and flexible.

We make use of a Python module called s3fs, which allows us to interact with files stored on Amazon’s S3

platform through Python commands.

We create an S3FileSystem object, which lets us interact with the S3 bucket as if it were a filesystem.

Hint

Note the anon=True argument, as attempting access to the HEASARC S3 bucket will fail without it!

s3 = S3FileSystem(anon=True)

Now we identify the specific files we want to download. The datalink table tells us the AWS S3 ‘path’ (the Uniform Resource Identifier, or URI) to each observation’s data directory, the RXTE documentation tells us that the automatically generated data products are stored in a subdirectory called ‘stdprod’, and the RXTE Guest Observer Facility (GOF) standard product guide shows us that the net light curves are named as:

xp{ObsID}_n2{energy-band}.lc - PCA

xh{ObsID}_n{array-number}{energy-band}.lc - HEXTE

We set up file patterns for the light curves we’re interested in, and then use the expand_path method of

our previously set-up S3 filesystem object to find all the files stored at each data-link’s destination that match the pattern. This is useful because the

RXTE datalinks we found might include sections of a particular observation that do not have standard products

generated, for instance, the slewing periods before/after the telescope was aligned on target.

lc_patts = ["xp*_n2*.lc.gz", "xh*_n0*.lc.gz", "xh*_n1*.lc.gz"]

all_file_patt = [

os.path.join(base_uri, "stdprod", fp)

for base_uri in data_links["aws"].value

for fp in lc_patts

]

val_file_uris = s3.expand_path(all_file_patt)

val_file_uris[:10]

['nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-01-00/stdprod/xp95437010100_n2a.lc.gz',

'nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-01-00/stdprod/xp95437010100_n2b.lc.gz',

'nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-01-00/stdprod/xp95437010100_n2c.lc.gz',

'nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-01-00/stdprod/xp95437010100_n2d.lc.gz',

'nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-01-00/stdprod/xp95437010100_n2e.lc.gz',

'nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-02-00/stdprod/xp95437010200_n2a.lc.gz',

'nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-02-00/stdprod/xp95437010200_n2b.lc.gz',

'nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-02-00/stdprod/xp95437010200_n2c.lc.gz',

'nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-02-00/stdprod/xp95437010200_n2d.lc.gz',

'nasa-heasarc/xte/data/archive/AO14/P95437/95437-01-02-00/stdprod/xp95437010200_n2e.lc.gz']

Now we can just use the get method of our S3 filesystem object to download all the valid light curve files!

lc_file_path = os.path.join(ROOT_DATA_DIR, "rxte_pregen_lc")

ret = s3.get(val_file_uris, lc_file_path)

3. Examining the archived RXTE light curves#

We just downloaded a lot of light curve files (over 500) - they are a set of light curves collected by PCA, HEXTE-0, and HEXTE-1 in several different energy bands, and now we ideally want to organize and examine them.

Collecting like light curves together#

Our first step is to pool together the file names that represent T5X2 light curves from a particular instrument in a particular energy band. Once we know which files belong together, we can easily visualize both the short and long-term variability of our source.

The information required to identify the light curve’s originating instrument is contained in the file names:

File name beginning with ‘xp’ - created from PCA data.

File name beginning with ‘xh’ - created from HEXTE data.

If the file name begins with ‘xh’ and the string after the ObsID and underscore is formatted as *0* then it is from the HEXTE-0 cluster.

Likewise, if it is formatted as *1* it is from the HEXTE-1 cluster

The file names also contain a reference to the energy band of the light curve:

PCA - final character before the file extension:

a: 2–9 keV

b: 2-4 keV

c: 4-9 keV

d: 9-20 keV

e: 20-40 keV

HEXTE - final character before the file extension:

a: 15–30 keV

b: 30-60 keV

c: 60-250 keV

We have already encoded this information in a function defined in the ‘Global Setup: Functions’ section near the top of this notebook, it takes a file name and returns the instrument, energy band, and ObsID.

For instance:

# Collect the names of all the light curve files we downloaded

all_lc_files = os.listdir(lc_file_path)

# The path of the file we're using to demonstrate

print(all_lc_files[0])

# Call the function to extract instrument, energy band, and ObsID from an

# RXTE light curve name

rxte_lc_inst_band_obs(all_lc_files[0])

xp95437010100_n2a.lc.gz

('PCA', <Quantity [2., 9.] keV>, '95437010100')

Loading the light curve files into Python#

HEASARC-archived RXTE light curves are stored as standard fits files, so the file

contents can be read in to memory using the Astropy fits.open() function.

For the purposes of this demonstration, however, we are not going to directly use

Astropy’s fits-file features. Instead, we will use the LightCurve data product class

implemented in the ‘X-ray: Generate and Analyse (XGA)’ Python module, as it provides a

convenient interface to much of the relevant information stored in a light curve

file. The LightCurve class also includes useful functions to visualize the

light curves.

As we iterate through the downloaded RXTE light curves and set up an XGA LightCurve instance for each, we take the additional step of grouping light curves with the same energy band and instrument.

They are stored in a nested dictionary, with top level keys corresponding to the instrument from which the light curves were generated, and the lower level keys being the standard energy bands for each instrument. Light curves are appended to a list, in the order that the files were listed, for each instrument-energy band combination.

like_lcs = {

"PCA": {"{0}-{1}keV".format(*e.value): [] for e in PCA_EN_BANDS.values()},

"HEXTE-0": {"{0}-{1}keV".format(*e.value): [] for e in HEXTE_EN_BANDS.values()},

"HEXTE-1": {"{0}-{1}keV".format(*e.value): [] for e in HEXTE_EN_BANDS.values()},

}

for cur_lc_file in all_lc_files:

cur_lc_path = os.path.join(lc_file_path, cur_lc_file)

cur_inst, cur_en_band, cur_oi = rxte_lc_inst_band_obs(cur_lc_file)

cur_lc = LightCurve(

cur_lc_path,

cur_oi,

cur_inst,

"",

"",

"",

rel_coord_quan,

Quantity(0, "arcmin"),

RXTE_AP_SIZES[cur_inst],

cur_en_band[0],

cur_en_band[1],

DEFAULT_TIME_BINS[cur_inst],

telescope="RXTE",

)

like_lcs[cur_inst]["{0}-{1}keV".format(*cur_en_band.value)].append(cur_lc)

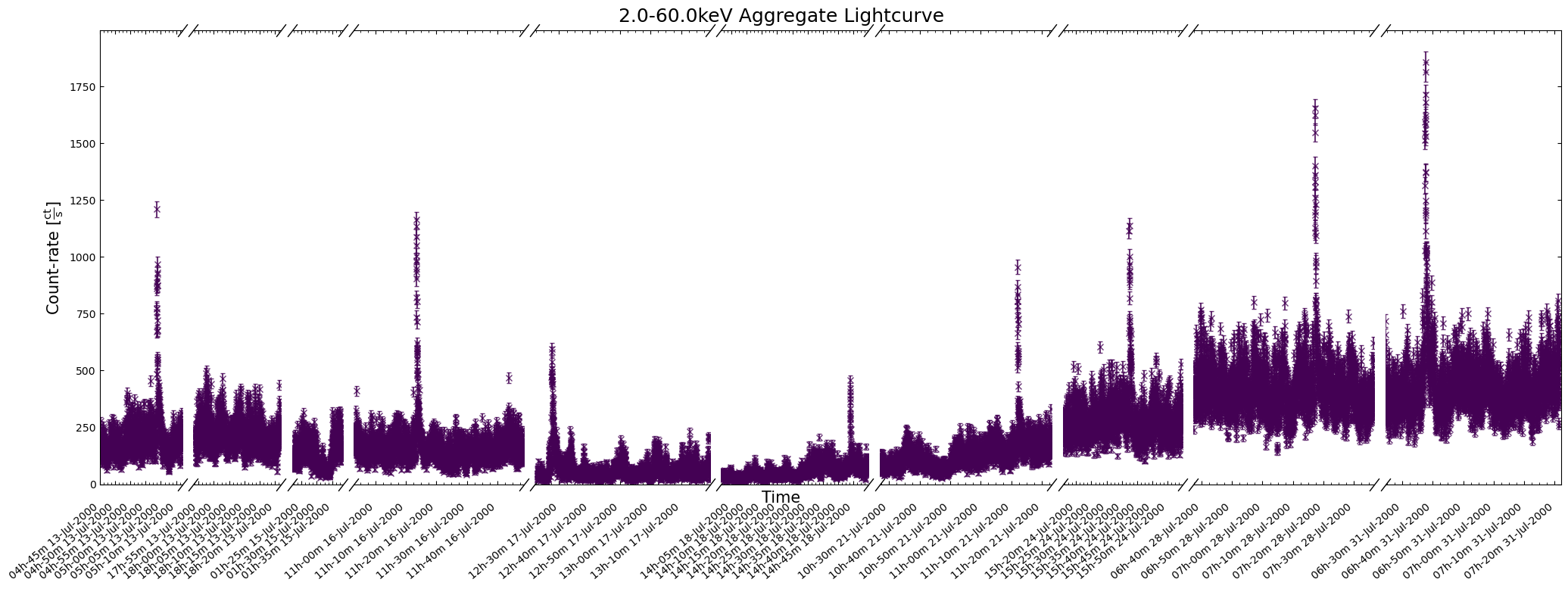

Examining long-term variability#

As we noted earlier, the RXTE observations that we selected were taken over the course of more than 10 years, and as such we have the opportunity to explore how the X-ray emission of T5X2 has altered in the long term (long term to a human anyway).

This is another reason that we chose to read in our archived light curves as XGA LightCurve objects; they make it easy to manage a large collection of light curves taken over a long period of time, organize them, and then extract some insights.

A list of XGA LightCurve objects can be used to set up another type of XGA

product, an AggregateLightCurve, which handles the management of a large, unwieldy

set of light curves. It will ensure that the light curves are sorted by time, will check

that they have consistent energy bands and time bins, and also provide a simple

way to access the data of all the constituent light curves together.

The AggregateLightCurve class also includes convenient visualization functions.

If the archived RXTE-PCA and HEXTE light curves had the same time bin size and energy

bands, we would be able to put them all into a single AggregateLightCurve, providing

convenient access to the data of all the light curves at once. We would also be able to

include light curves from other telescopes, which would also be sorted and made easily

accessible by the AggregateLightCurve object.

However, as the time bin sizes and energy bands are not consistent between these

instruments, we’ll have to set up a few different AggregateLightCurve objects:

# Very ugly definition of a nested dictionary of AggregateLightCurve objects

agg_lcs = {

"PCA": {

"{0}-{1}keV".format(*e.value): AggregateLightCurve(

like_lcs["PCA"]["{0}-{1}keV".format(*e.value)]

)

for e in PCA_EN_BANDS.values()

},

"HEXTE": {

"{0}-{1}keV".format(*e.value): AggregateLightCurve(

like_lcs["HEXTE-0"]["{0}-{1}keV".format(*e.value)]

+ like_lcs["HEXTE-1"]["{0}-{1}keV".format(*e.value)]

)

for e in HEXTE_EN_BANDS.values()

},

}

agg_lcs

{'PCA': {'2.0-9.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33a1241340>,

'2.0-4.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33a107b9b0>,

'4.0-9.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33a0eab5f0>,

'9.0-20.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33a3e7e480>,

'20.0-40.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33a0d27d40>},

'HEXTE': {'15.0-30.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33a3e8e270>,

'30.0-60.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33a0d27740>,

'60.0-250.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33a0acddf0>}}

Interacting with aggregate light curves#

What you want to do with your aggregated light curve and the long-term variability that it describes (depending on what your source is and how many times it was observed, of course) will depend heavily on your particular science case.

We will now demonstrate how to access and interact with the data, using the 2–9 keV PCA aggregate light curve as an example.

demo_agg_lc = agg_lcs["PCA"]["2.0-9.0keV"]

demo_agg_lc

<xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33a1241340>

Which observations contributed data?#

As AggregateLightCurves are particularly well suited for providing an interface to

the time variability of a source that has been observed many times, such as T5X2, we

might conceivably lose track of which observations (denoted by their ObsID)

contributed data.

In this demonstration, for instance, we just identified the relevant observations and downloaded them, without closely examining which ObsIDs we were actually using.

The obs_ids property will return a dictionary that stores the relevant ObsIDs, with

the dictionary keys being the names of the telescopes from which the data were taken:

pprint(demo_agg_lc.obs_ids, compact=True)

{'RXTE': ['50138030100', '50138030101', '50138030200', '50138030300',

'50138030400', '50138030500', '50054060100', '50054060101',

'50054060200', '50054060201', '50054060202', '50054060300',

'50054060301', '50054060401', '50054060402', '50054060400',

'50054060403', '50054060500', '50054060501', '50054060600',

'50054060601', '50054060700', '50054060701', '50054060802',

'50054060900', '50054060901', '50054061000', '50054061001',

'50054061100', '50054061101', '50054061102', '50054061200',

'50054061201', '50054061203', '50054061202', '50054061300',

'50054061301', '50054061400', '50054061401', '50054061500',

'50054061501', '50054061502', '50054061503', '70412010100',

'70412010200', '70412010300', '95437010100', '95437010200',

'95437010201', '95437010300', '95437010301', '95437010302',

'95437010303', '95437010400', '95437010401', '95437010500',

'95437010501', '954370106000', '95437010600']}

Both the telescope names and the instruments associated with each ObsID are accessible through their own properties:

demo_agg_lc.telescopes

['RXTE']

pprint(demo_agg_lc.instruments, compact=True)

{'RXTE': {'50054060100': ['PCA'],

'50054060101': ['PCA'],

'50054060200': ['PCA'],

'50054060201': ['PCA'],

'50054060202': ['PCA'],

'50054060300': ['PCA'],

'50054060301': ['PCA'],

'50054060400': ['PCA'],

'50054060401': ['PCA'],

'50054060402': ['PCA'],

'50054060403': ['PCA'],

'50054060500': ['PCA'],

'50054060501': ['PCA'],

'50054060600': ['PCA'],

'50054060601': ['PCA'],

'50054060700': ['PCA'],

'50054060701': ['PCA'],

'50054060802': ['PCA'],

'50054060900': ['PCA'],

'50054060901': ['PCA'],

'50054061000': ['PCA'],

'50054061001': ['PCA'],

'50054061100': ['PCA'],

'50054061101': ['PCA'],

'50054061102': ['PCA'],

'50054061200': ['PCA'],

'50054061201': ['PCA'],

'50054061202': ['PCA'],

'50054061203': ['PCA'],

'50054061300': ['PCA'],

'50054061301': ['PCA'],

'50054061400': ['PCA'],

'50054061401': ['PCA'],

'50054061500': ['PCA'],

'50054061501': ['PCA'],

'50054061502': ['PCA'],

'50054061503': ['PCA'],

'50138030100': ['PCA'],

'50138030101': ['PCA'],

'50138030200': ['PCA'],

'50138030300': ['PCA'],

'50138030400': ['PCA'],

'50138030500': ['PCA'],

'70412010100': ['PCA'],

'70412010200': ['PCA'],

'70412010300': ['PCA'],

'95437010100': ['PCA'],

'95437010200': ['PCA'],

'95437010201': ['PCA'],

'95437010300': ['PCA'],

'95437010301': ['PCA'],

'95437010302': ['PCA'],

'95437010303': ['PCA'],

'95437010400': ['PCA'],

'95437010401': ['PCA'],

'95437010500': ['PCA'],

'95437010501': ['PCA'],

'95437010600': ['PCA'],

'954370106000': ['PCA']}}

demo_agg_lc.associated_instruments

{'RXTE': ['PCA']}

Retrieving constituent light curves#

Though the AggregateLightCurve object provides a convenient way to access the data of all the light curves that it contains, you might sometimes want to retrieve the individual LightCurve objects.

Using the get_lightcurves() method, you can retrieve LightCurve objects for

particular time chunks:

demo_agg_lc.get_lightcurves(0)

<xga.products.lightcurve.LightCurve at 0x7f33a0ea9070>

If the AggregateLightCurve contains data from multiple instruments, telescopes, or

ObsIDs, then the inst, telescope, and obs_id arguments can be passed.

Accessing all data#

demo_agg_lc.get_data()

(<Quantity [ 94.79163, 72.70727, 96.5273 , ..., 1238.7705 , 1230.9957 ,

1212.9932 ] ct / s>,

<Quantity [2.505628, 2.216513, 2.526862, ..., 8.773673, 8.746537, 8.682692] ct / s>,

array([2.06081059e+08, 2.06081075e+08, 2.06081091e+08, ...,

5.30035603e+08, 5.30035619e+08, 5.30035635e+08], shape=(13915,)),

array([ 0, 0, 0, ..., 58, 58, 58], shape=(13915,)))

Accessing data for a specific time interval#

This part of the demonstration will show you how to access data within specific time intervals of interest - we define the following start and stop times based on an interesting time window discussed in M. Linares et al. (2012):

demo_agg_wind_start = Time("2010-10-16 09:00:00")

demo_agg_wind_stop = Time("2010-10-18 12:00:00")

An AggregateLightCurve’s constituent products are organized into discrete ‘time chunks’, defined by a start and stop time that do not overlap with any other ‘time chunk’. Time chunks are sorted so that their ‘time chunk ID’, which uniquely identifies them, represents where they are in the sorted list of time chunks (i.e., time chunk 1 contains data taken after time chunk 0, and so on).

Looking at the time_chunk_ids property shows us how many time chunks this

set of PCA light curves is divided into:

demo_agg_lc.time_chunk_ids

array([ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16,

17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33,

34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50,

51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58])

The time intervals represented by those IDs are also accessible, with the first column

containing the start time of the time chunk, and the second column containing the

stop time. This information is available both in the form of seconds

from the reference time (time_chunks), and the other in the form of explicit

datetime objects (datetime_chunks):

demo_agg_lc.time_chunks[:10]

demo_agg_lc.datetime_chunks[:10]

array([[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 13, 4, 45, 15, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 13, 5, 12, 11, 562431)],

[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 13, 17, 53, 31, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 13, 18, 22, 3, 562431)],

[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 15, 1, 23, 39, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 15, 1, 38, 51, 562431)],

[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 16, 10, 52, 59, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 16, 11, 47, 23, 562431)],

[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 17, 12, 23, 23, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 17, 13, 18, 3, 562431)],

[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 18, 14, 0, 27, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 18, 14, 48, 27, 562431)],

[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 21, 10, 26, 51, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 21, 11, 21, 47, 562431)],

[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 24, 15, 15, 39, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 24, 15, 53, 31, 562431)],

[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 28, 6, 38, 51, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 28, 7, 34, 51, 562431)],

[datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 31, 6, 23, 23, 562431),

datetime.datetime(2000, 7, 31, 7, 20, 27, 562431)]], dtype=object)

We can use the obs_ids_within_interval() method to identify which observations

took place within a given time interval:

demo_agg_lc.obs_ids_within_interval(demo_agg_wind_start, demo_agg_wind_stop)

{'RXTE': ['95437010400',

'95437010401',

'95437010500',

'95437010501',

'954370106000']}

The default behavior of this method is to

return ObsIDs of observations that overlap with the interval, but if you

pass over_run=False then only ObsIDs of observations that took place entirely within

the specified interval will be returned:

demo_agg_lc.obs_ids_within_interval(

demo_agg_wind_start, demo_agg_wind_stop, over_run=False

)

{'RXTE': ['95437010400', '95437010401', '95437010500', '95437010501']}

That method makes use of the time_chunk_ids_within_interval() method, which you can

use in exactly the same way to retrieve the time chunk IDs that are part of a given

time interval:

demo_agg_lc.time_chunk_ids_within_interval(demo_agg_wind_start, demo_agg_wind_stop)

array([53, 54, 55, 56, 57])

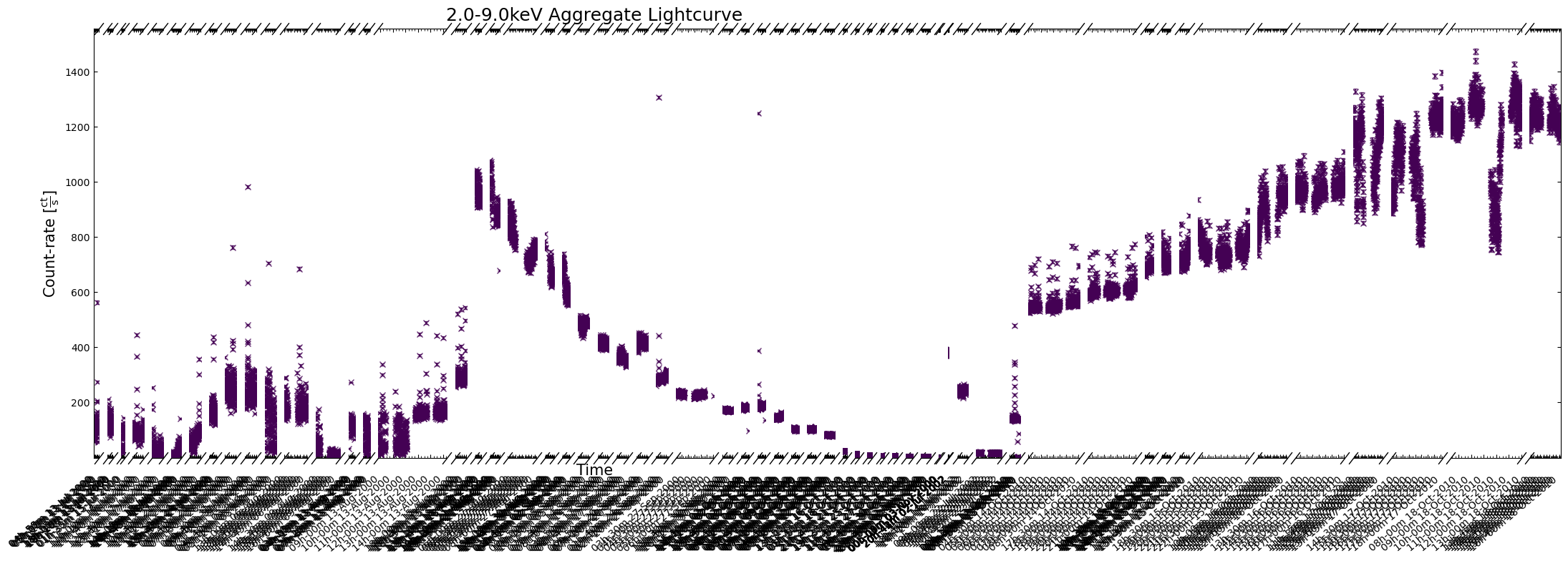

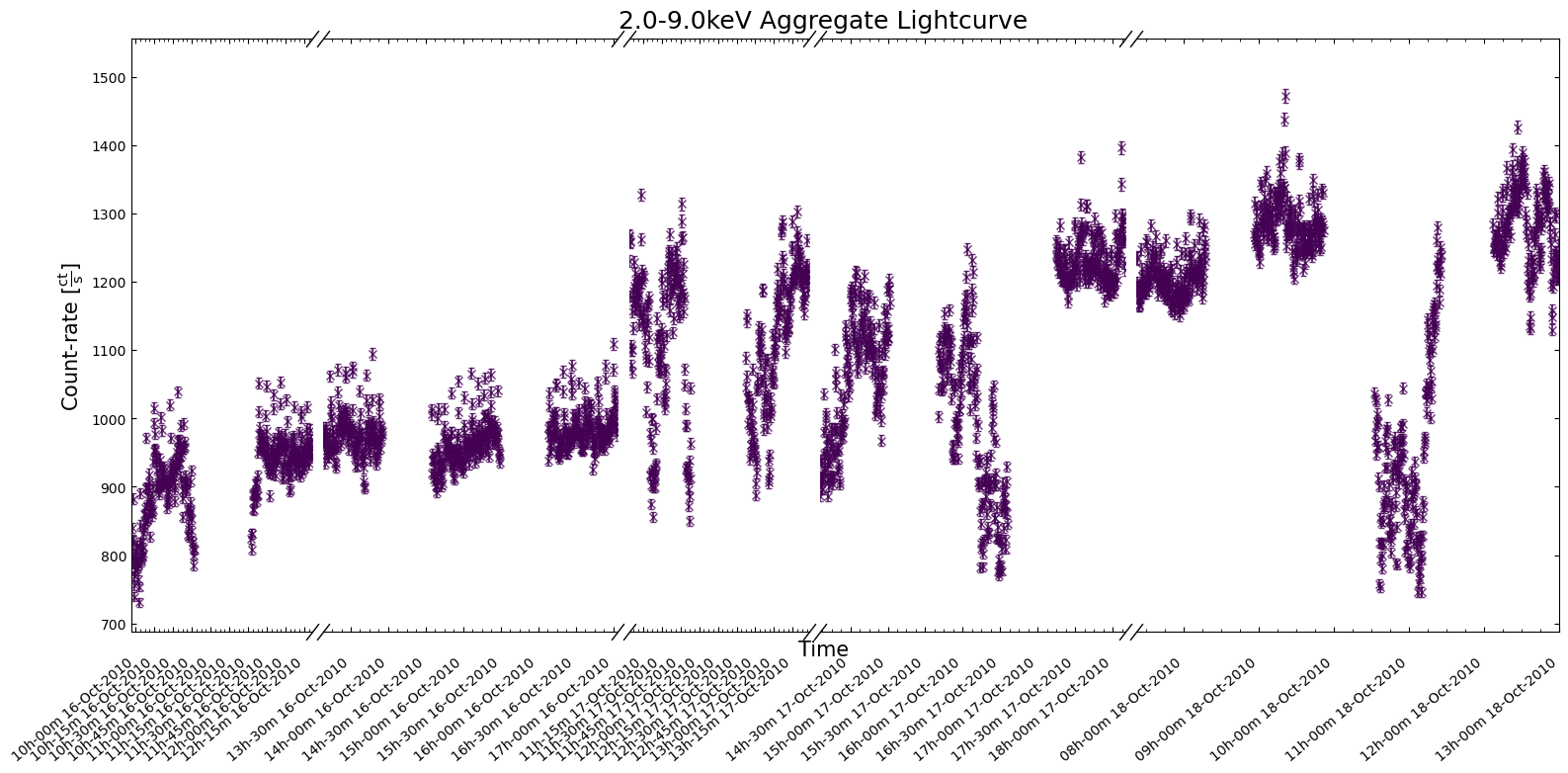

Visualizing aggregated light curves#

We can use the view() method to quickly produce a plot of the aggregated light curve, but if your

dataset covers a particularly long time period, you can end up with a very unhelpful figure:

demo_agg_lc.view(show_legend=False)

To address the problems with the last figure, we could increase its size by passing a custom value to

the figsize argument (e.g. (30, 6)), or you could specify a particular time window to focus on:

demo_agg_lc.view(

interval_start=demo_agg_wind_start,

interval_end=demo_agg_wind_stop,

show_legend=False,

)

4. Generating new RXTE-PCA light curves#

The time bin size of archived RXTE light curves is relatively coarse, particularly compared to the time resolution that the PCA and HEXTE instruments can achieve. Given the type of object we are investigating, we might reasonably expect that significant emission variations might be happening at smaller time scales than our time bin size.

Our inspiration for this demonstration, the work by M. Linares et al. (2012), generated RXTE-PCA light curves with different time bin sizes (2-second and 1-second bins) to search for different features.

Also, while light curves generated within several different energy bands are included in the RXTE archive, many science cases will require that light curves be generated in very specific energy bands.

The archived light curves have gotten our exploration of T5X2’s variable X-ray emission off to an excellent start, but clearly we also need to be able to generate new versions that are tailored to our specific requirements.

This section of the notebook will go through the steps required to make RXTE-PCA light curves from scratch, focusing on the two requirements mentioned above; smaller time bins, and control over light curve energy bands.

Downloading specific files for our RXTE observations#

Unfortunately, our first step is to spend even more time downloading data from the RXTE archive, as we previously targeted only the archived light curve files. Making new light curves requires all the original data and many spacecraft files.

The RXTE archive does not contain equivalents of the pre-cleaned event files found in many other HEASARC-hosted high-energy telescope archives, which is why we will have to perform the calibration and reduction processes from scratch.

We could use the Astroquery Heasarc.download_data() object to download whole directories for all observations, just as

we demonstrated in the first part of Section 2, e.g.:

Heasarc.download_data(data_links, host="aws", location=ROOT_DATA_DIR)

However, to save some downloading time and storage space, we will take a slightly more complex approach and download only the files we’re going to need to reprocess the observations and generate new light curves.

We defined a list of files and directories that we do not need to download (DOWN_EXCLUDE) in the

‘Global Setup: Constants’ section near the top of the notebook, and we will use it in combination with

the s3fs Python module to list and filter the files in each observation’s directory.

Then we will use s3fs to download just those files that we need:

for dl in data_links:

cur_uri = dl["aws"]

all_cont = np.array(

s3.ls(

cur_uri,

)

)

down_mask = np.all(np.char.find(all_cont, DOWN_EXCLUDE[..., None]).T == -1, axis=1)

down_cont = all_cont[down_mask].tolist()

infer_oi = os.path.dirname(cur_uri).split("/")[-1]

cur_out = os.path.join(ROOT_DATA_DIR, infer_oi)

os.makedirs(cur_out, exist_ok=True)

for cur_down_cont in down_cont:

s3.get(cur_down_cont, cur_out, recursive=True, on_error="ignore")

Note

We note that it is generally recommended to reprocess high-energy event lists taken from HEASARC mission archives from scratch, as it means that the latest calibration and filtering procedures can be applied.

Running the RXTE-PCA preparation pipeline#

A convenient pipeline to prepare RXTE-PCA data for use is included in the HEASoft

package - pcaprepobsid. It will take us from raw RXTE-PCA data to the science-ready

data and filter files required to generate light curves in a later step - the PCA team

recommended the default configuration of the pipeline for general scientific use.

Now we have to talk about the slightly unusual nature of RXTE-PCA observations; the PCA proportional counter units could be simultaneously read out in various ‘data modes’. That meant that some limitations of the detectors and electronics could be mitigated by using data from the different modes in different parts of your analysis.

At least 10 different data modes could be requested by the observer, but the ‘Standard-1’ and ‘Standard-2’ modes were active for every observation.

The RXTE-PCA instrument had very high temporal and moderate spectral resolutions, but both could not be true at the same time. The ‘Standard-1’ and ‘Standard-2’ modes ‘binned’ the readout from the detectors in two different ways:

Standard 1 - accumulated the combined readout from all detector channels, with a time resolution of 0.125 seconds.

Standard 2 - accumulated the 256 detector channels binned into 129 ‘Standard 2’ channels, with a time resolution of 16 seconds.

Note

The Standard-2 data mode is the most commonly used and supported.

We are using the HEASoftPy interface to the pcaprepobsid task, but wrap it in

another function (defined in the ‘Global Setup’ section) that makes it easier for us

to run the processing of different observation’s PCA data in parallel.

As the initial processing of raw data is the step in any analysis most likely to error, we have made sure that the wrapper function returns information on whether the processing failed, the logs, and the relevant ObsID. That makes it easy for us to identify problem ObsIDs.

Now we run the pipeline for all of our selected RXTE observations:

with mp.Pool(NUM_CORES) as p:

arg_combs = [[oi, os.path.join(OUT_PATH, oi), rel_coord] for oi in rel_obsids]

pipe_result = p.starmap(process_rxte_pca, arg_combs)

pca_pipe_problem_ois = [

all_out[0]

for all_out in pipe_result

if not all_out[2]

or "Task pcaprepobsid 1.4 terminating with status -1" in str(all_out[1])

]

rel_obsids = [oi for oi in rel_obsids if oi not in pca_pipe_problem_ois]

pca_pipe_problem_ois

/opt/envs/heasoft/lib/python3.12/multiprocessing/popen_fork.py:66: DeprecationWarning: This process (pid=2039) is multi-threaded, use of fork() may lead to deadlocks in the child.

self.pid = os.fork()

['50054-06-08-00', '50054-06-08-01', '50054-06-08-03', '50054-06-08-04']

Setting up RXTE-PCA good time interval (GTI) files#

The RXTE-PCA data for our observations of T5X2 are now (sort of) ready for use!

Though the observation data files have been prepared, we do still need to define

‘good time interval’ (GTI) files for each observation. These will combine the filter

file produced by pcaprepobsid, which is determined by various spacecraft orbit and

electronics housekeeping considerations, with another user-defined filtering expression.

The user-defined filter is highly customizable, but we will use the expression recommended (see the note below for the source of this recommendation) to apply ‘basic’ screening to RXTE-PCA observations of a bright target:

# Recommended filtering expression from RXTE cookbook pages

filt_expr = "(ELV > 4) .AND. (OFFSET < 0.1) .AND. (NUM_PCU_ON > 0 .AND. NUM_PCU_ON < 6)"

Breaking down the terms of the filter expression:

ELV > 4 - Ensures that the target is above the Earth’s horizon. More conservative limits (e.g., > 10) will make sure that ‘bright earth’ is fully screened out, but this value is sufficient for many cases.

OFFSET < 0.1 - Makes sure that PCA is pointed at the target to within 0.1 degrees.

NUM_PCU_ON > 0 .AND. NUM_PCU_ON < 6 - Ensures that at least one of the five proportional counter units is active.

See also

An in-depth discussion of how to screen/filter RXTE-PCA data is available on the HEASARC website.

Now that we’ve settled on the filtering expression, the maketime HEASoft task can

be used to make the final GTI files for each observation. Another wrapper function to

the HEASoftPy maketime interface is declared, and we again execute the task in parallel:

with mp.Pool(NUM_CORES) as p:

arg_combs = [[oi, os.path.join(OUT_PATH, oi), filt_expr] for oi in rel_obsids]

gti_result = p.starmap(gen_pca_gti, arg_combs)

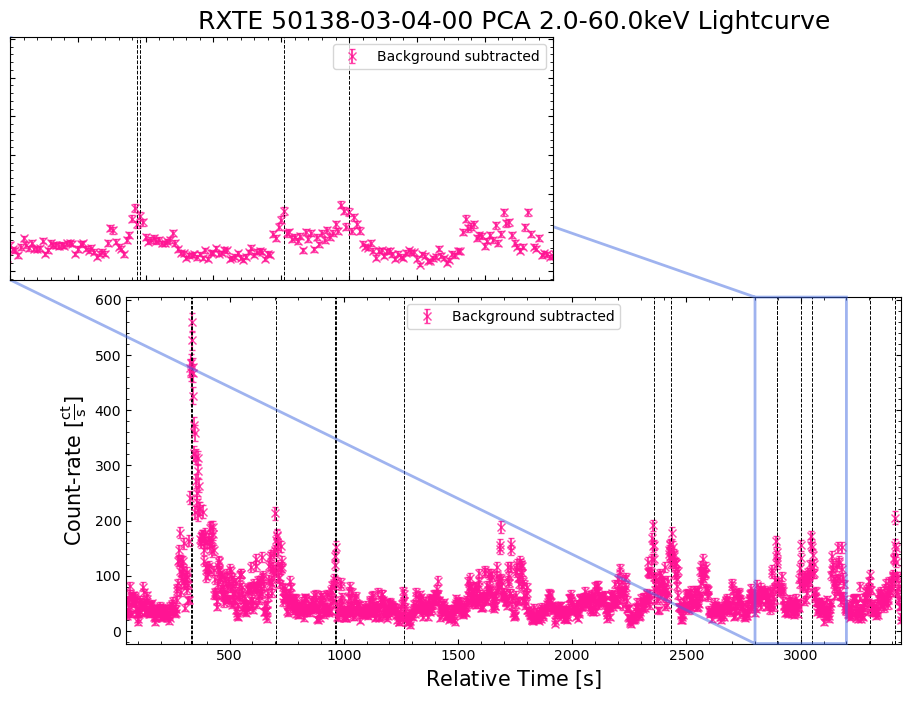

New light curves within custom energy bounds#

Recall that we want to generate two categories of custom light curves; those within custom energy bands, and those with time resolution better than 16 seconds.

We’ll tackle the custom energy band light curves first, as they use the more common

data mode, ‘Standard-2’. The generation of these light curves will be

straightforward, as HEASoft includes a task called pcaextlc2 for exactly this

purpose.

As previously mentioned, the RXTE-PCA instrument is made up of five separate proportional counter units (PCUs). The state and reliability of those PCUs varied significantly over the lifetime of the mission, so we do not necessarily use want to use data from all five.

PCU 2 was considered the most reliable, and so we are going to use that for our newly generated light curves.

chos_pcu_id = "2"

Note

The default behaviour of PCA light curve generation functions in HEASoft is to use all available PCUs, in which case a combined light curve is produced. We have set up our wrapper functions for the light curve generation tasks so that a single PCU or a list of PCUs can be passed.

The slight sticking point is that pcaextlc2 takes arguments of upper and

lower absolute channel limits to specify which band the output light curve should be

generated within. Our particular science case will inform us which energy bands

we should look at, but we have to convert them to channels ourselves.

Caution

It is important to make a distinction between RXTE-PCA ‘Standard-2’ channels (which have values between 0 and 128) and PCA’s absolute channels (which have values between 0 and 255). Standard-2 is a binned data mode, and its channels represent combinations of absolute channels.

We need to convert our energy bands (whatever we decide they will be) to the equivalent absolute channels. HEASARC provides a table that describes the mapping of absolute channels to ‘Standard-2’ channels and energies at different epochs in the life of the telescope.

You could quite easily use this to convert from your target energy band to the absolute channel limits, but when dealing with many archival observations from different epochs, it is more convenient to implement a more automated solution.

Building RXTE-PCA response files#

That automated method of converting from energy to channel involves:

Generating new RXTE-PCA response files for each observation

Using the “EBOUNDS” table of responses to move from energy to ‘Standard-2’ channel

Finally, using the known binning of ‘Standard-2’ channels to arrive at the absolute channel limits.

We note that as some, but not all, ‘Standard-2’ channels correspond to a range of absolute channels, the mean value of the absolute channel range is used, and rounded down to the nearest integer for the lower limit, and rounded up to the nearest integer for the upper limit.

Rather than using the HEASoft tool specifically for generating RXTE-PCA RMFs, we

cheat a little and use the HEASoft tool designed to produce spectra (and supporting

files) from RXTE-PCA data; pcaextspect2.

The advantage of this is that pcaextspect2 will automatically handle the combination

of responses from different PCUs, which would not be necessary for our use of PCU 2, but

makes it easier to use multiple PCUs if you choose.

As with the other HEASoft tasks, we write a wrapper function for the HEASoftPy interface in order to run the task in parallel:

with mp.Pool(NUM_CORES) as p:

arg_combs = [[oi, os.path.join(OUT_PATH, oi), chos_pcu_id] for oi in rel_obsids]

rsp_result = p.starmap(gen_pca_s2_spec_resp, arg_combs)

Note

The response files produced by pcaextspect2 are a combination of the ARF and RMF

products commonly seen in high energy astrophysics data.

To make the next step easier, we set up a template for the path to the response files we just generated:

rsp_path_temp = os.path.join(OUT_PATH, "{oi}", "rxte-pca-pcu{sp}-{oi}.rsp")

Generating the light curves#

Now that the response files have been generated, we can create our new light curves!

The first step is to decide on the lower and upper limits of the energy band(s) we want the light curve(s) to be drawn from. We also define the time bin size to use, remembering that the ‘Standard-2’ data mode required for applying energy bounds has a minimum time resolution of 16 seconds.

We choose to build light curves in three custom energy bands:

2-10 keV

10-30 keV

2-60 keV

These selections are fairly arbitrary and aren’t physically justified, but yours

should be informed by your science case. If you are using this code as a template

for your own analysis, you could add more energy bands to the new_lc_en_bnds list,

and they would be generated as well.

We choose a time bin size of 16 seconds, as this is a bright source and we wish for the best possible temporal resolution.

new_lc_en_bnds = [

Quantity([2, 10], "keV"),

Quantity([10, 30], "keV"),

Quantity([2, 60], "keV"),

]

en_time_bin_size = Quantity(16, "s")

Now we can run the pcaextlc2 task to generate the light curves. We note that the

wrapper function we create for the HEASoftPy interface to pcaextlc2 includes

extra processing steps that use the supplied lower and upper energy limits and

response file to determine the absolute channel limits. Please examine the

wrapper function defined in the ‘Global Setup’ section for more details.

form_sel_pcu = pca_pcu_check(chos_pcu_id)

with mp.Pool(NUM_CORES) as p:

arg_combs = [

[

oi,

os.path.join(OUT_PATH, oi),

*cur_bnds,

rsp_path_temp.format(oi=oi, sp=form_sel_pcu),

en_time_bin_size,

chos_pcu_id,

]

for oi in rel_obsids

for cur_bnds in new_lc_en_bnds

]

lc_en_result = p.starmap(gen_pca_s2_light_curve, arg_combs)

Finally, we set up a template for the path to the light curves we just generated:

lc_path_temp = os.path.join(

OUT_PATH, "{oi}", "rxte-pca-pcu{sp}-{oi}-en{lo}_{hi}keV-tb{tb}s-lightcurve.fits"

)

Loading the light curves into Python#

Our shiny new custom-energy-band light curves can be loaded into convenient XGA LightCurve objects, just as the archived light curves were - they will once again provide a convenient interface to the data, and some nice visualization capabilities.

As we set up the energy bands in which to generate new light curves as a list of Astropy quantities (which you may add to or remove from for your own purposes), and we know the format of the output file names (as we set that up), we can dynamically load in those light curves.

Iterating through the energy bounds, and the relevant ObsIDs, every new light curve file gets its own LightCurve object, and is then appended to a list in a dictionary with energy bands as keys.

From there, one aggregate light curve per energy band is set up and also stored in a dictionary for easy (and dynamic) access:

gen_en_bnd_lcs = {}

for cur_bnd in new_lc_en_bnds:

cur_bnd_key = "{0}-{1}keV".format(*cur_bnd.value)

gen_en_bnd_lcs.setdefault(cur_bnd_key, [])

for oi in rel_obsids:

cur_lc_path = lc_path_temp.format(

oi=oi,

sp=form_sel_pcu,

tb=en_time_bin_size.value,

lo=cur_bnd[0].value,

hi=cur_bnd[1].value,

)

cur_lc = LightCurve(

cur_lc_path,

oi,

"PCA",

"",

"",

"",

rel_coord_quan,

Quantity(0, "arcmin"),

RXTE_AP_SIZES["PCA"],

*cur_bnd,

en_time_bin_size,

telescope="RXTE",

)

gen_en_bnd_lcs[cur_bnd_key].append(cur_lc)

# Set up the aggregate light curves

agg_gen_en_bnd_lcs = {

cur_bnd_key: AggregateLightCurve(cur_bnd_lcs)

for cur_bnd_key, cur_bnd_lcs in gen_en_bnd_lcs.items()

}

# Show the structure of the agg_gen_en_bnd_lcs dictionary

agg_gen_en_bnd_lcs

{'2.0-10.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f337b43fb30>,

'10.0-30.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f337b5538f0>,

'2.0-60.0keV': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f337bd0ea20>}

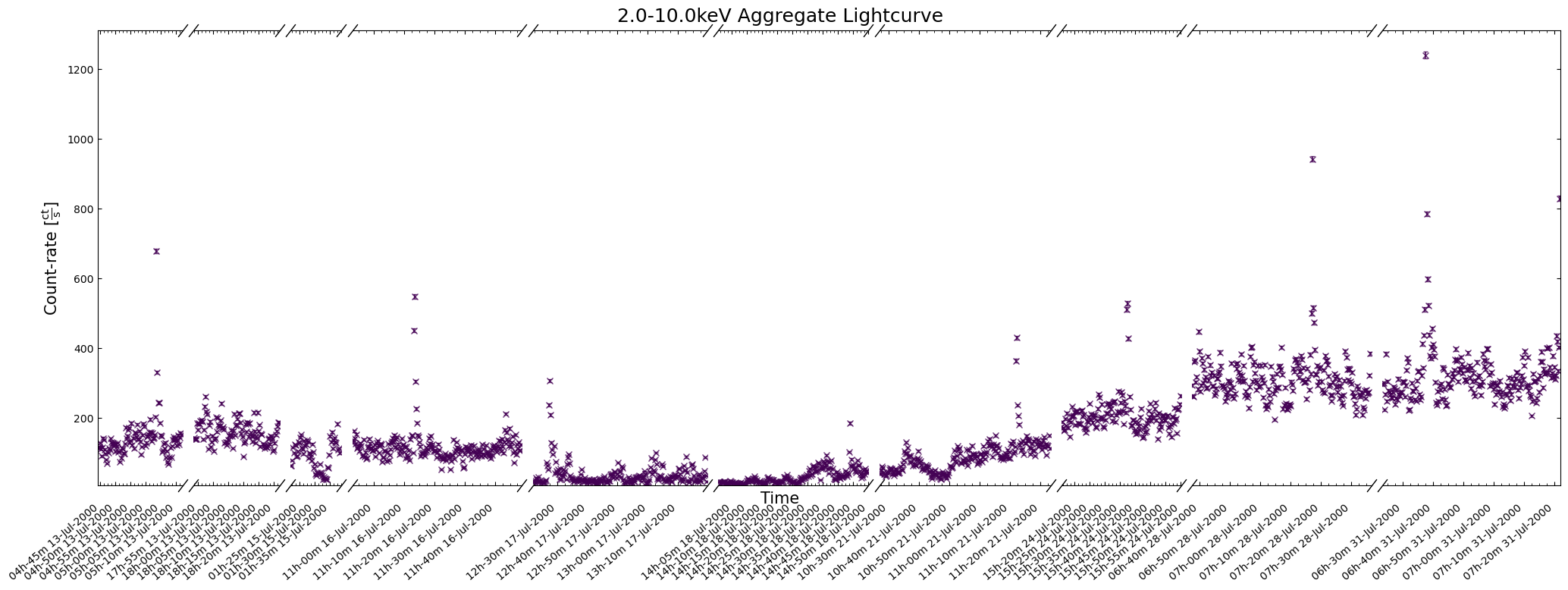

Visualizing new custom-energy-band light curves#

The first thing to do is to take a look at one of our new light curves to make sure that (on the surface at least) everything looks reasonably sensible.

You should really examine the whole aggregation of new light curves in a particular energy band, but for demonstrative purposes we’ll look at a two-week time window:

agg_gen_en_bnd_lcs["2.0-10.0keV"].view(

show_legend=False,

figsize=(18, 6),

interval_start=Time("2000-07-13 05:00:00"),

interval_end=Time("2000-08-03"),

)

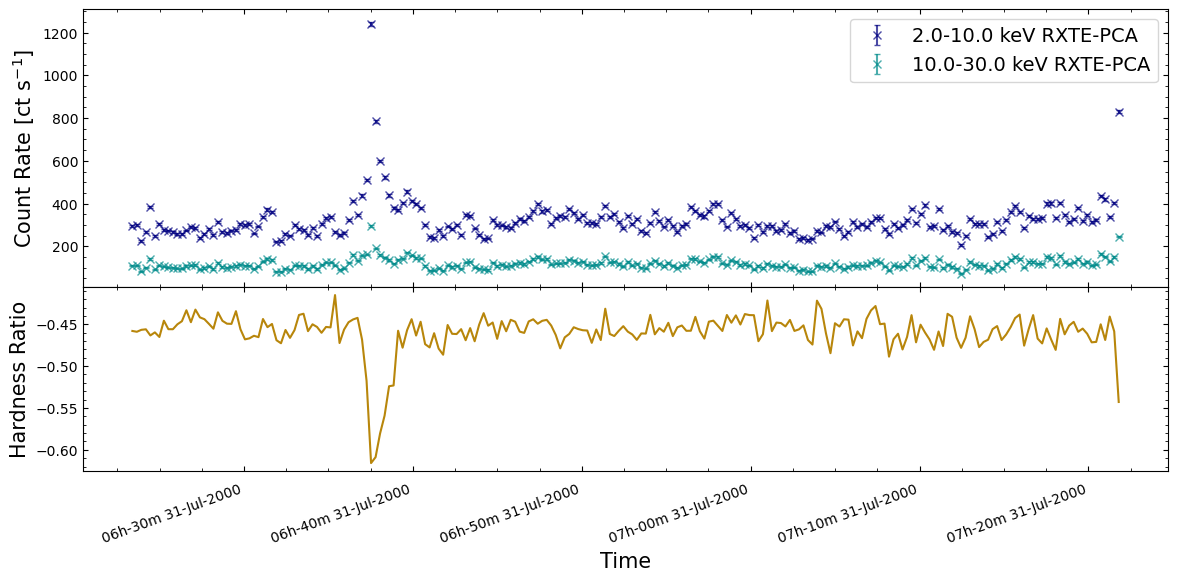

Calculating and examining hardness ratio curves#

Being able to generate light curves within energy bands of our choice will be a useful tool for many science cases; for instance, sometimes you wish to target particular emission mechanisms that produce X-ray photons of a certain energy.

Sometimes you take a broader view and simply want to know if the variation in emission is distinct between the ‘soft’ X-ray band to the ‘hard’ X-ray band (exactly what defines ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ will vary depending on your specialization, the telescope you’re using, and sometimes just how you feel on a particular day).

In either case it is often useful to visualize a ‘hardness curve’ which shows how the ‘hardness ratio’ of two energy bands changes with time. There are multiple definitions of the hardness ratio, but for our purposes we’ll use:

Where \(\rm{HR}_{{H:S}}\) is the hard-to-soft band ratio, \(F_{H}\) is the flux in the hard band, and \(F_{S}\) is the flux in the soft band.

Hardness curves can be considered as a short-cut to the sort of information extracted from time-resolved spectroscopy (which is outside the scope of this tutorial).

See also

Our calculation of hardness ratio is fairly simplistic - there are better approaches that take into account the often-Poissian nature of X-ray light curve data points, and calculate uncertainties on the ratio. See the Chandra Source Catalog hardness ratio page for an example.

We will choose a single observation to visualize the hardness ratio curve for, just for ease of viewing; there is no reason you could not use the same approach for all observations.

Three energy-bands were chosen when we generated the new light curves earlier in this section, and we will choose the 2.0–10 keV as the soft band, and the 10.0–30 keV as the hard band:

hard_rat_ch_id = 9

lo_en_demo_lc = agg_gen_en_bnd_lcs["2.0-10.0keV"].get_lightcurves(hard_rat_ch_id)

hi_en_demo_lc = agg_gen_en_bnd_lcs["10.0-30.0keV"].get_lightcurves(hard_rat_ch_id)

hard_rat = (hi_en_demo_lc.count_rate - lo_en_demo_lc.count_rate) / (

hi_en_demo_lc.count_rate + lo_en_demo_lc.count_rate

)

The figure we produce plots the two light curves on the same axis, and then the calculated hardness curve on a second axis below. As such, we can both see the original behaviors evident in the light curves, and how the hardness ratio changes for those behaviors.

We find that the hardness ratio is effectively constant for much of the chosen observation, and that the approximately constant value indicates that more emission is detected in the soft band than the hard.

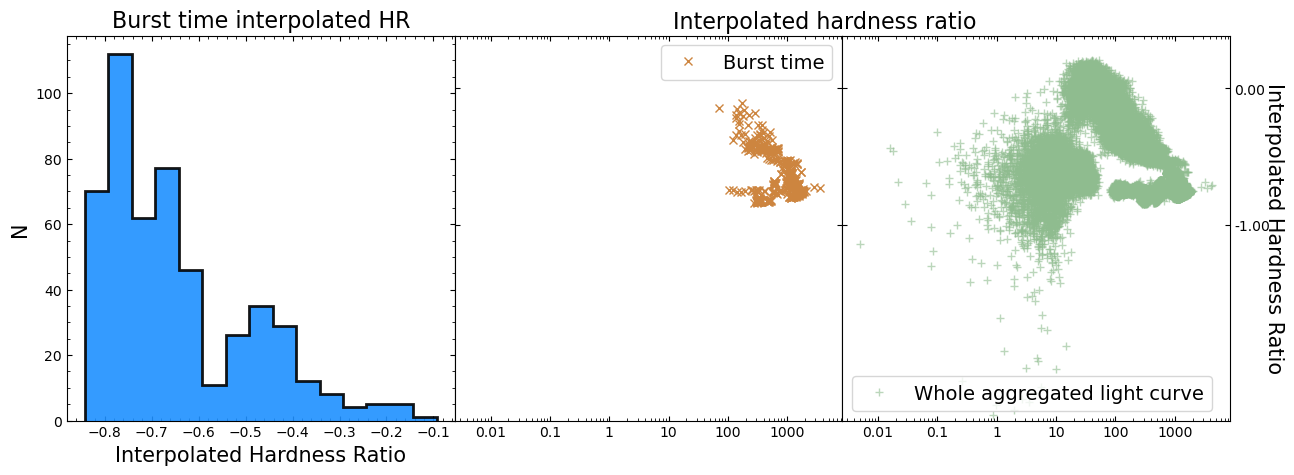

Interestingly, when we see a very large increase in emission from a burst, the hardness ratio drops significantly, becoming even more negative. Thinking back to the hardness ratio definition, it is clear that these large bursts emit more photons in the soft-band (2–10 keV in this case) than the hard-band (10–30 keV).

Interpreting this sort of behavior is heavily dependent on your science case and the astrophysics involved in whatever object you are studying. However, our initial hypothesis here might be that the large bursts originate from a different mechanism than the smaller variations in emission we see elsewhere in the light curves.

New light curves with high temporal resolution#

Addressing our other reason for generating new light curves, we can now use the ‘Standard-1’ data mode to achieve a much finer temporal resolution than the ‘Standard-2’ mode.

We select a time bin size of 2 seconds to match the temporal resolution of the RXTE-PCA light curves that M. Linares et al. (2012) used to identify T5X2 bursts:

new_lc_time_bin_sizes = Quantity([1, 2], "s")

This is still considerably oversampling the potential time resolution for ‘Standard-1’ data, as it is binned into 0.125 second chunks.

Generating new light curves#

Unlike when we made new light curves within a custom energy band, we don’t need to worry about converting from energy to channels as, unfortunately, ‘Standard-1’ data does not contain any spectral information.

Warning

Though ‘Standard-1’ data contains no spectral information (as it consists of the

combined readout from all detector channels) the pcaextlc1 HEASoft task does

take minimum and maximum channel arguments - do not use them.

Here we wrap and run the pcaextlc1 task in parallel, just as we did pcaextlc2 in the last section:

form_sel_pcu = pca_pcu_check(chos_pcu_id)

with mp.Pool(NUM_CORES) as p:

arg_combs = [

[

oi,

os.path.join(OUT_PATH, oi),

cur_tsz,

chos_pcu_id,

]

for oi in rel_obsids

for cur_tsz in new_lc_time_bin_sizes

]

lc_result = p.starmap(gen_pca_s1_light_curve, arg_combs)

/opt/envs/heasoft/lib/python3.12/multiprocessing/popen_fork.py:66: DeprecationWarning: This process (pid=2039) is multi-threaded, use of fork() may lead to deadlocks in the child.

self.pid = os.fork()

Finally, we set up a template for the path to the light curves we just generated:

lc_hi_res_path_temp = os.path.join(

OUT_PATH, "{oi}", "rxte-pca-pcu{sp}-{oi}-enALL-tb{tb}s-lightcurve.fits"

)

Loading the light curves into Python#

Just as we did for the archived light curves and the newly generated energy-bound light curves, we will load the new files into XGA LightCurve objects, and from there into an AggregateLightCurve per time-bin-size:

gen_hi_time_res_lcs = {}

for cur_tsz in new_lc_time_bin_sizes:

cur_tsz_key = cur_tsz.to_string().replace(" ", "")

gen_hi_time_res_lcs.setdefault(cur_tsz_key, [])

for oi in rel_obsids:

cur_lc_path = lc_hi_res_path_temp.format(

oi=oi, sp=form_sel_pcu, tb=cur_tsz.value

)

cur_lc = LightCurve(

cur_lc_path,

oi,

"PCA",

"",

"",

"",

rel_coord_quan,

Quantity(0, "arcmin"),

RXTE_AP_SIZES["PCA"],

Quantity(2, "keV"),

Quantity(60, "keV"),

cur_tsz,

telescope="RXTE",

)

gen_hi_time_res_lcs[cur_tsz_key].append(cur_lc)

# Set up the aggregate light curves

agg_gen_hi_time_res_lcs = {

cur_tsz_key: AggregateLightCurve(cur_tsz_lcs)

for cur_tsz_key, cur_tsz_lcs in gen_hi_time_res_lcs.items()

}

# Show the structure of the agg_gen_hi_time_res_lcs dictionary

agg_gen_hi_time_res_lcs

{'1.0s': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33cce366c0>,

'2.0s': <xga.products.lightcurve.AggregateLightCurve at 0x7f33ccd89340>}

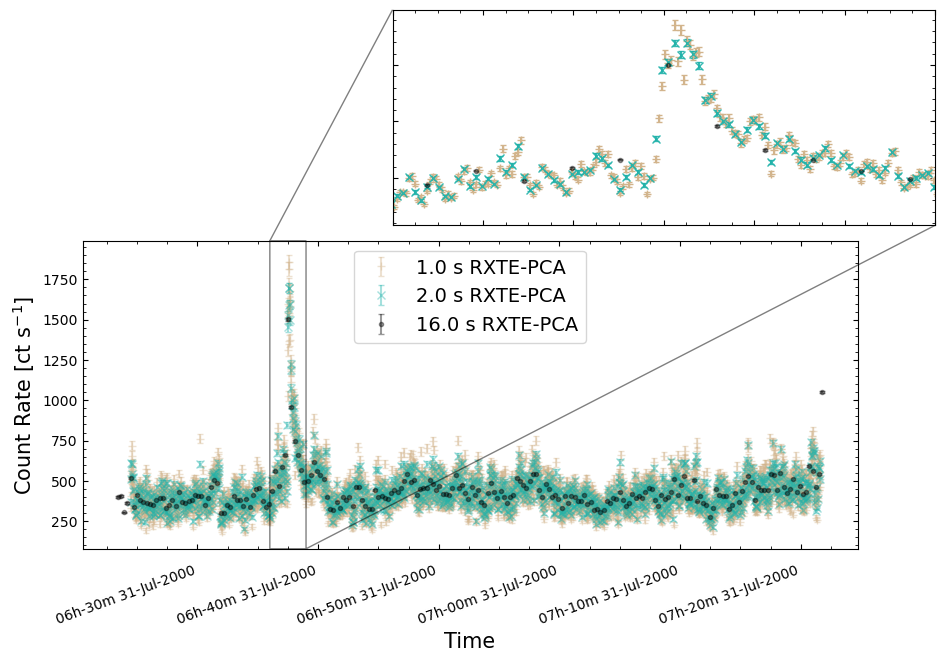

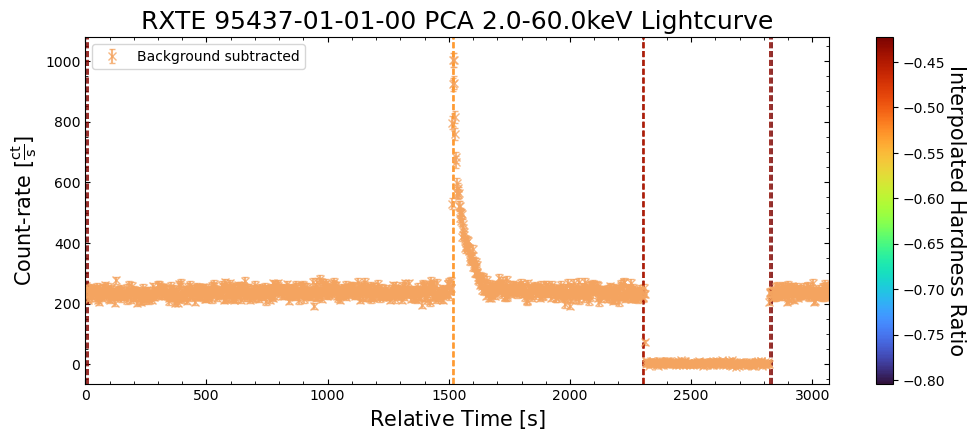

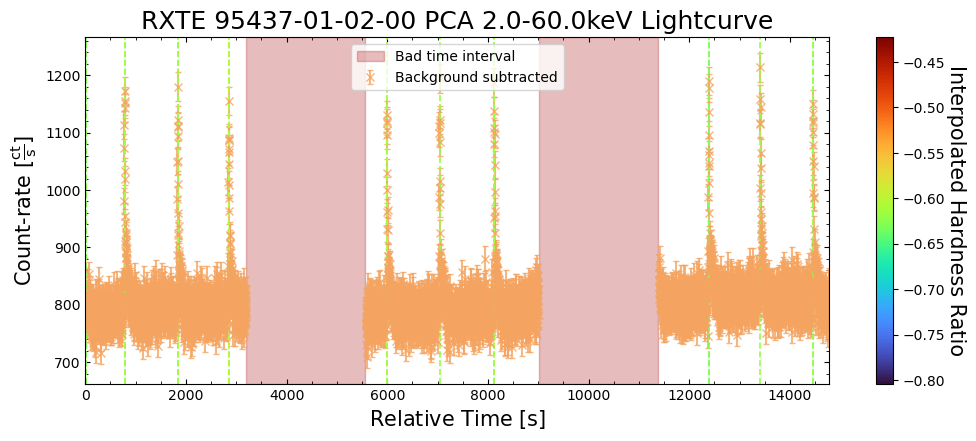

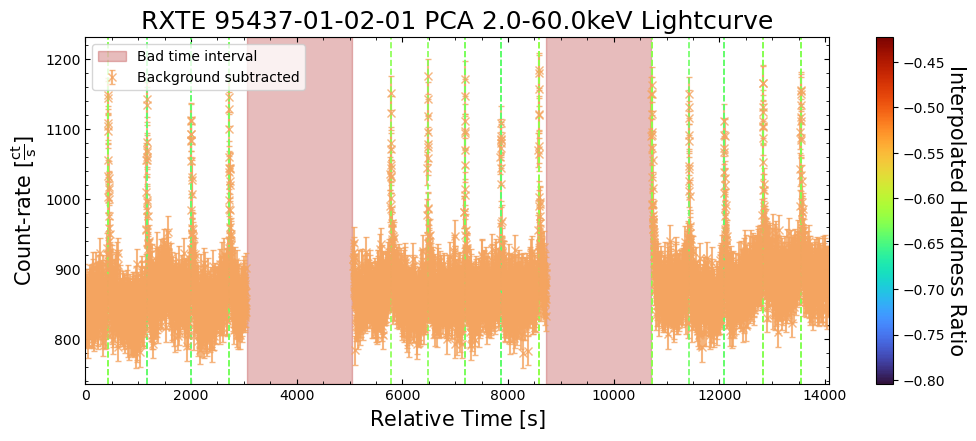

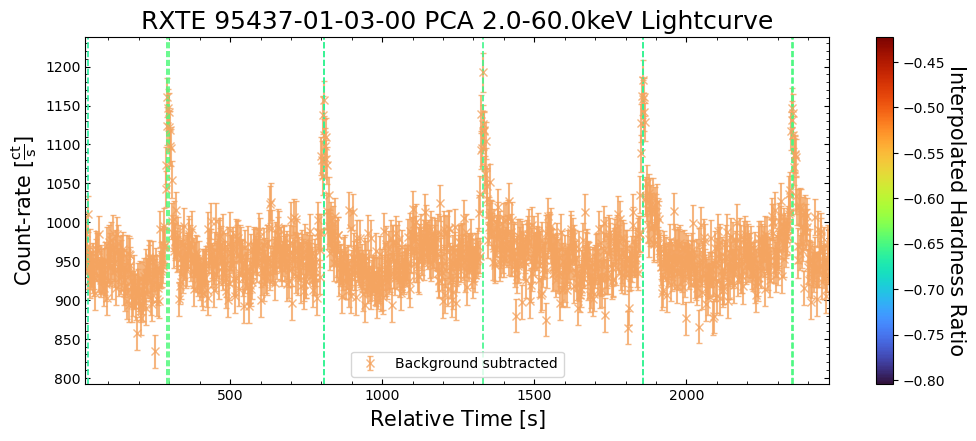

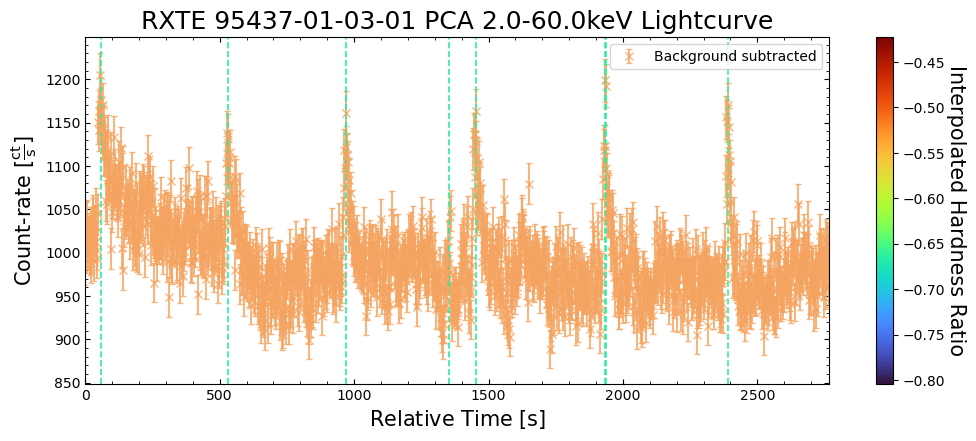

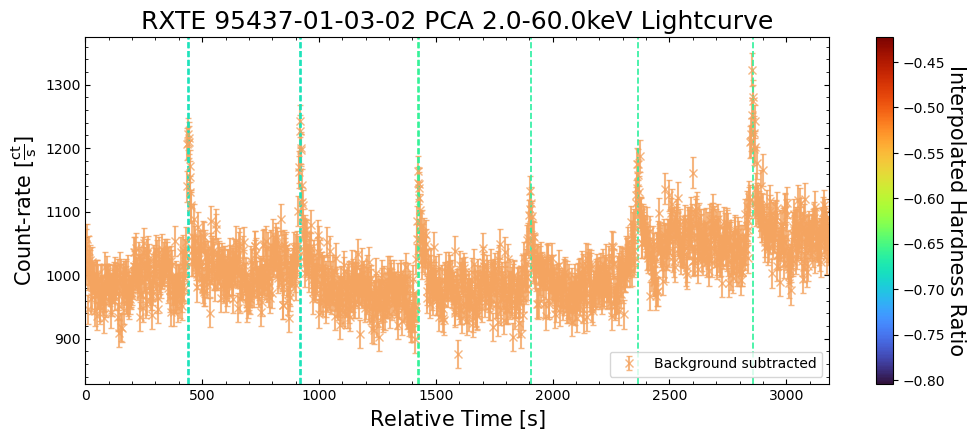

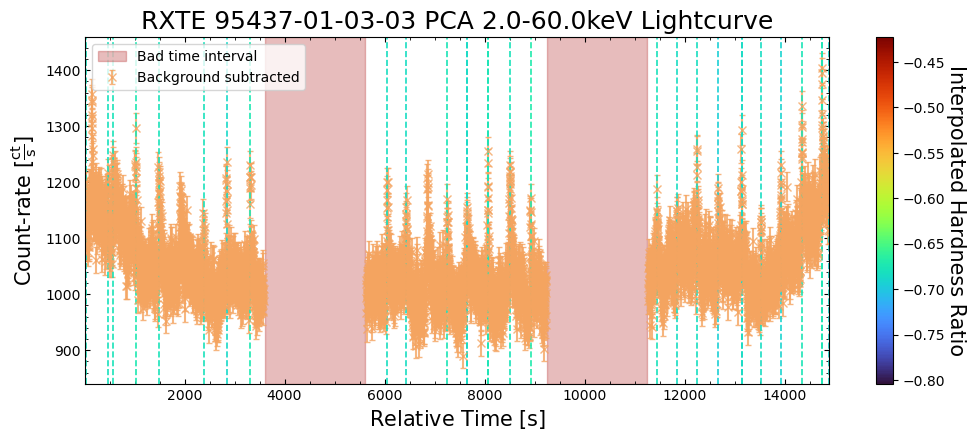

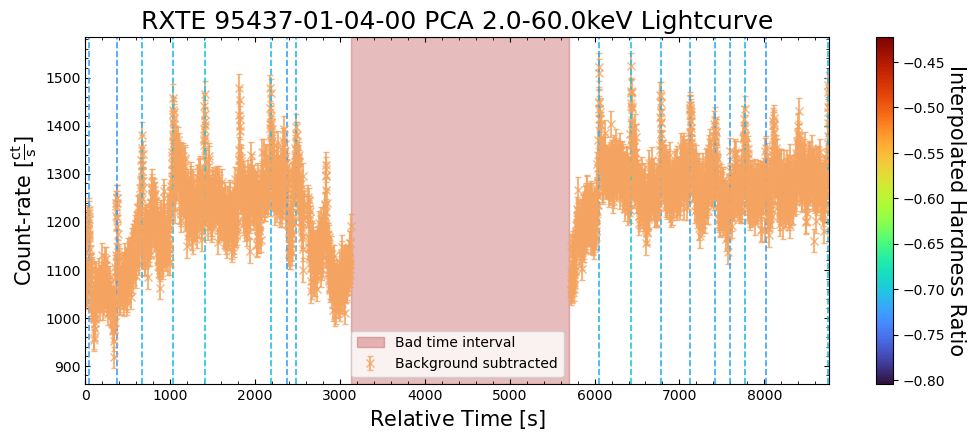

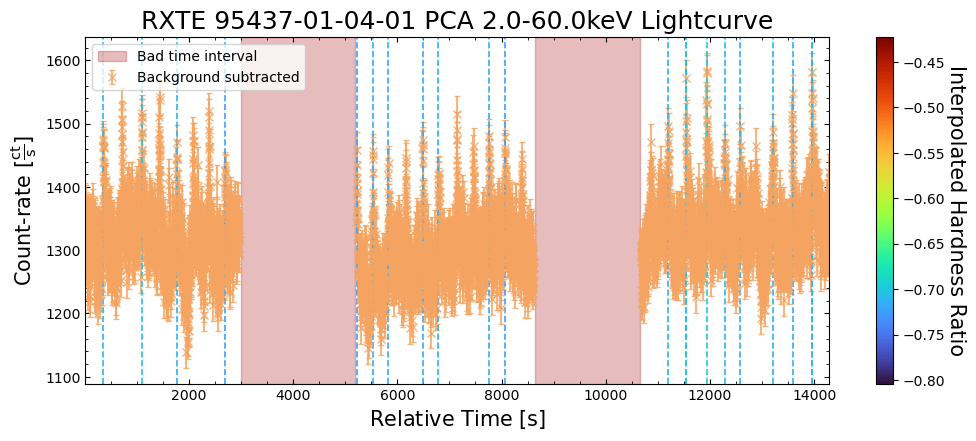

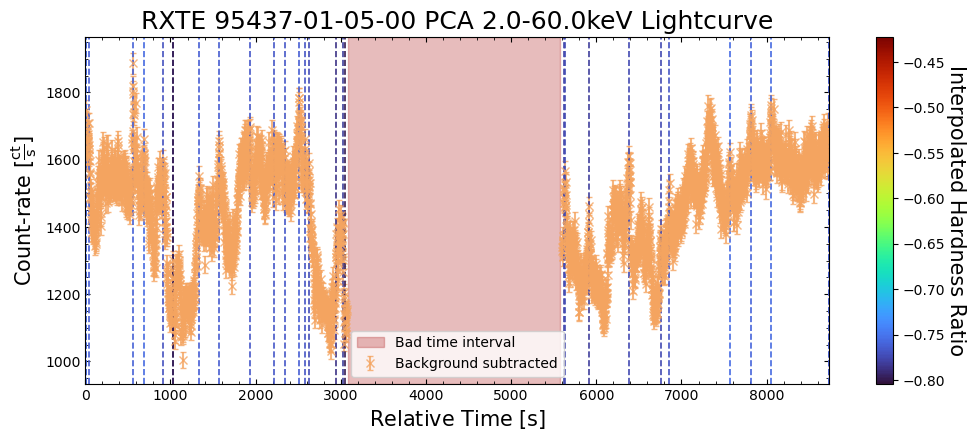

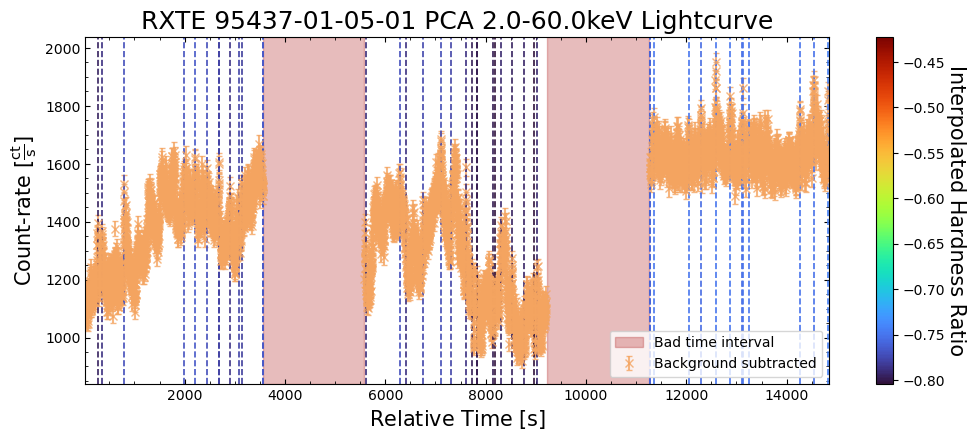

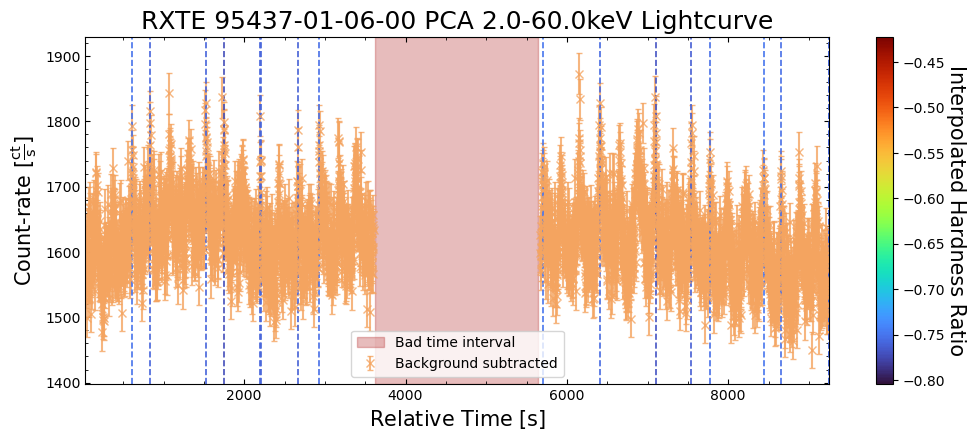

Visualizing new higher time-resolution light curves#

We can now visually examine the new higher-temporal-resolution light curves. It is always good practice to visually examine your data, as it can help you spot any potential problems, as well as any interesting features.

There are new light curves with both one-second and two-second time bins, but here we will select the highest-resolution option to examine.

Rather than looking at the whole aggregate light curve, we choose a small date range to increase the interpretability of the output figure:

To give a sense of how the finer temporal bins might affect our interpretation of our source’s (T5X2) time-varying behavior, we are going to plot a single observation’s light curve generated with one, two, and sixteen second time bins.

The sixteen-second time bin light curve is in the same energy band as the two fine-temporal-resolution light curves (2–60 keV), and was generated in the “New light curves within custom energy bounds” section of this notebook.

We access the relevant aggregate light curves and extract a single light curve from each - the selected light curves are all from the same time bin (thus observation), as we wish to compare like-to-like:

tbin_comp_ch_id = 9

onesec_demo_lc = agg_gen_hi_time_res_lcs["1.0s"].get_lightcurves(tbin_comp_ch_id)

twosec_demo_lc = agg_gen_hi_time_res_lcs["2.0s"].get_lightcurves(tbin_comp_ch_id)

sixteensec_demo_lc = agg_gen_en_bnd_lcs["2.0-60.0keV"].get_lightcurves(tbin_comp_ch_id)

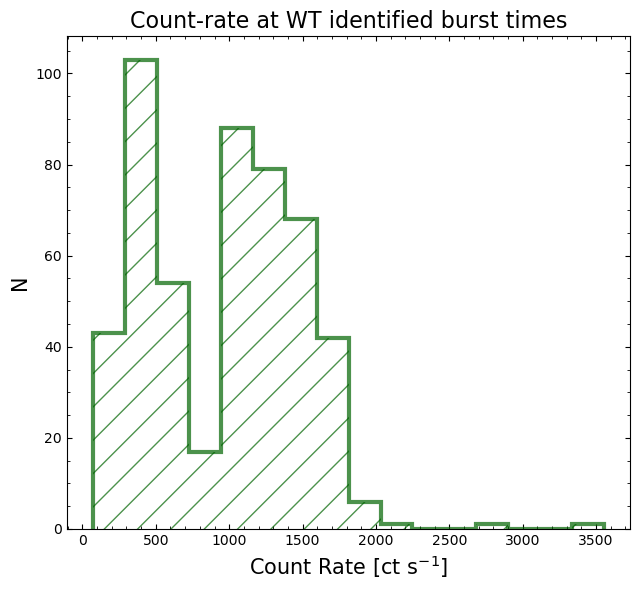

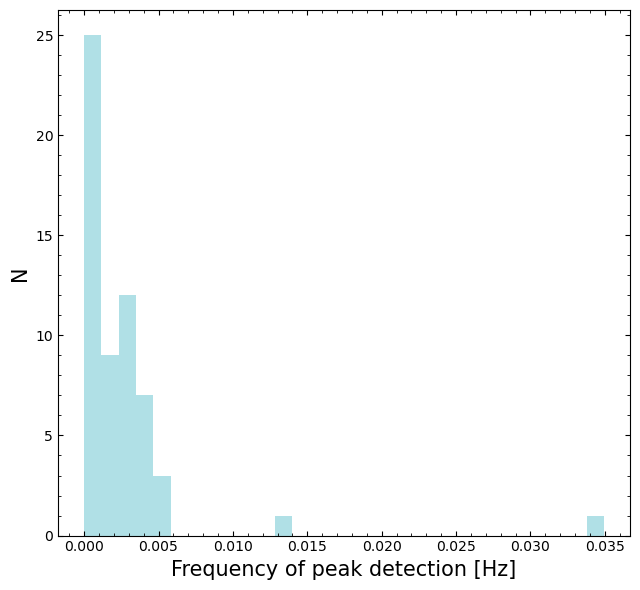

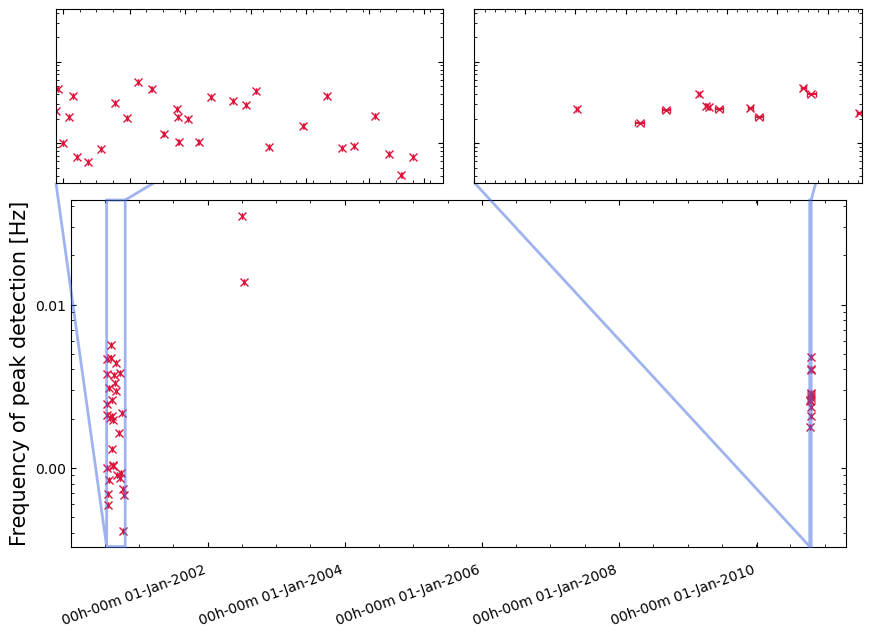

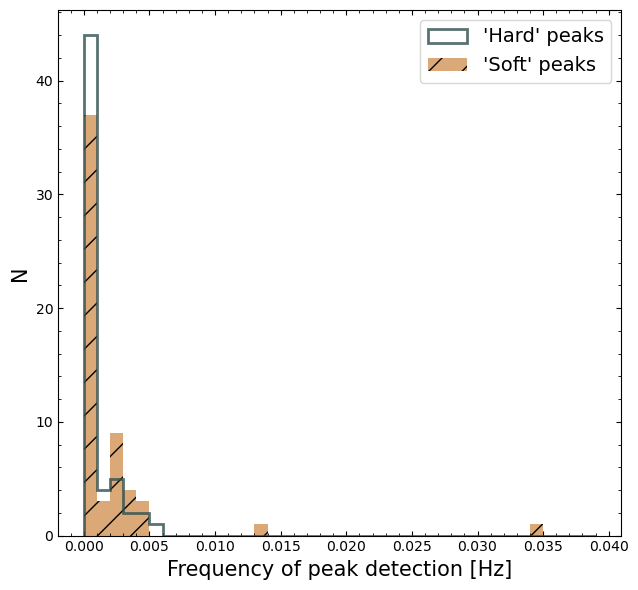

Plotting the light curves on the same axis is an excellent demonstration of why we bothered to make new light curves with finer time binning in the first place.